Hyundai Santa Fe 8-speed dual clutch transmission extreme endurance test

I just flogged Hyundai’s eight-speed dual clutch transmission, in the driveway from hell. Here’s what I learned in the process.

In this report I thrash Hyundai's new 8sp DCT in the diesel 2021 Santa Fe for 12 rounds up the driveway from hell (tight, twisty and 5m ascent for 20-ish metres of lineal concrete).

Before attempting to murder the DCT in the bloodiest possibly way, here is some mountain climbing context to set the scene.

Having driven the mid-spec Elite Santa Fe for a week now, with the Highlander in a few weeks, the full review is nearly here.

In the meantime, it strikes me that some of you really like the idea of buying a Santa Fe diesel (or its under-the-skin twin, the Kia Sorento diesel, which shares exactly the same powertrain) but some of you are somehow disinclined to buy a vehicle with a dual-clutch transmission - so scary - mainly thanks to Ford’s terrifying efforts, with its horrific ‘PowerShift’ dual-clutch transmission, and its appalling reliability. You may recall I was somewhat thorough in my coverage of that Power Shitshow.

Hyundai-Kia’s latest eight-speed DCT, by comparison, is a wet clutch system (meaning, the clutches operate in an oil bath) - and the oil is fed into an external convective cooler to manage overheating.

This is a completely separate oil system - as in, the oil that cools the clutches is separate from the oil that lubricates the gears.

Clutch durability is really simple to understand - all you need to know is that heat kills clutches. We’re about to put that to the test. Quite a severe one.

I want to see for myself (and show you) whether or not I can induce a near-death heat experience in the Santa Fe diesel dual clutch, by doing some severe real-world reversing.

And if it does go poopy in its trousers I’ll be reporting that, and doubtless there will be a terse telephone call with Hyundai, the temperature of which will be somewhat less than the clutch pack.

If nothing else, you know how I always say: ‘Never buy a demonstrator.’? Yeah. Well, this would be one reason why. (Actually, it should be fine. I’m told the transmission has inbuilt thermal overload protection, but let’s find out anyway.)

USEFUL LINKS FOR BUYING & USING TRANSMISSIONS

The truth about servicing automatic transmissions (even the sealed ones) >>

Sealed for life transmissions: an epic fail coming your way >>

Ultimate Transmission Guide: Manual, Auto, Dual-Clutch and CVT >>

Heavy towing with automatic transmissions: what not to do >>

SPECIAL SANTA FE & SORENTO REPORT: Dual clutch transmissions, towing and heavy-duty uphill reversing >>

High Slopes

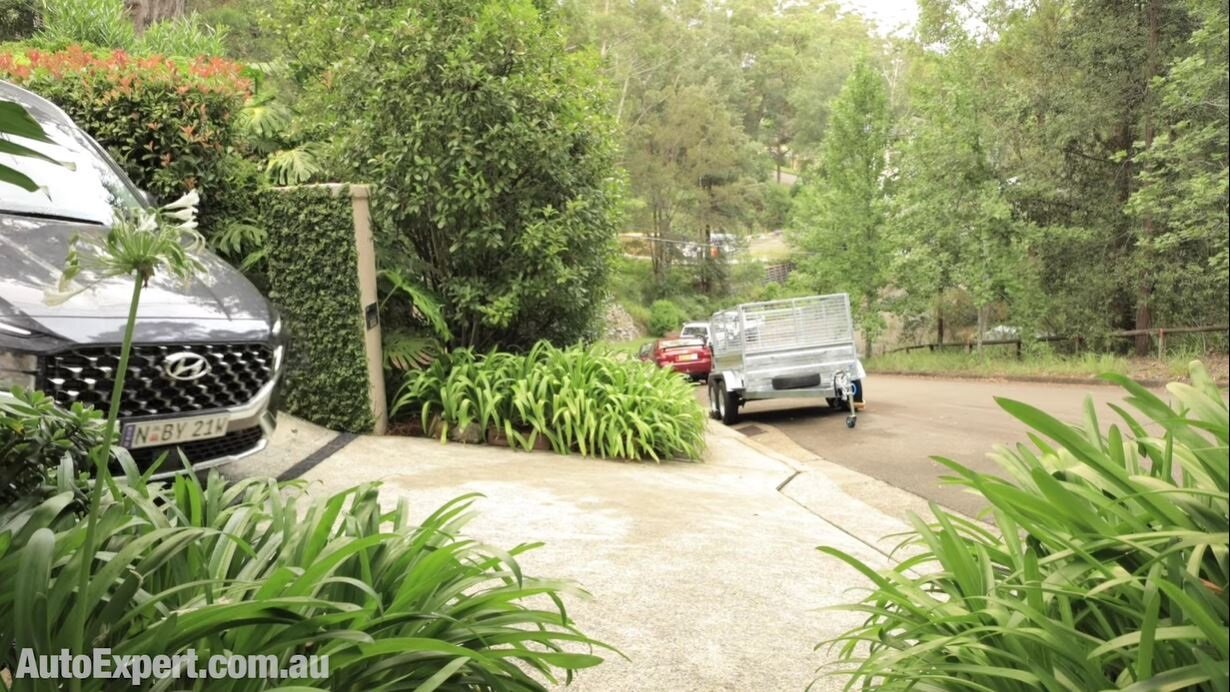

As you can see, this is my somewhat arduous driveway - it’s the price I pay for living on the North Face of the Eiger. Albeit in Australia, surround by poisonous spiders, flesh-eating insects and bogans.

It’s mid-20 degrees Celsius on this day where I’ve put the test vehicle through 12 laps of the concrete which rises about five metres of vertical height for about 30 metres of lineal concrete. With minimal rest.

Some clutch slipping is inevitable. The mission is to see if it will stand the test where I’m going to add maximum heat and see if the Santa Fe can take it. Let’s roll.

This either fails in a ball of flames with a trite call to Hyundai, or I end up triumphant.

And while we’re at it, reversing into your driveway, so as to exit driving forward, is the best way to do it. You should be a fan. It reduces the chance of unexpected something crossing behind your reversing vehicle.

This is a fairly complex driveway. It’s an S-shape on a dramatic slope, to the point you won’t back a trailer up here.

This test may not seem severe, but I assure you, moving this 2000kg vehicle five metres vertically against gravity requires roughly 500 kilojoules of energy - enough energy in heat to heat a block of steel from room temperature to about 250 Celsius. It’s enough to temper hardened steel.

This requires a lot of energy. You just can’t see it. It’s the same amount of kinetic energy the car would have travelling at about 120km/h down the freeway.

After 12 laps, and not putting a scratch on Hyundai’s test car, the Santa Fe passes the sniff test. There are no warning lights on the dash and I cannot get even a whiff of the smell of failure (burning clutch).

My AutoExpert AFFORDABLE ROADSIDE ASSISTANCE PACKAGE

If you’re sick of paying through the neck for roadside assistance I’ve teamed up with 24/7 to offer AutoExpert readers nationwide roadside assistance from just $69 annually, plus there’s NO JOINING FEE

Full details here >>

Some considerations

Hyunda-Kia’s latest eight-speed DCT, by comparison, is a wet clutch system (meaning, the clutches operate in an oil bath) - and the oil is fed into an external convective cooler to manage overheating.

This is a completely separate oil system - as in, the oil that cools the clutches is separate from the oil that lubricates the gears.

Clutch durability is really simple to understand - all you need to know is that heat kills clutches. We’re about to put that to the test. Quite a severe one.

In case you didn’t believe me before, this should prove a definitive result on heavy load endurance and duty cycle tolerance for this transmission.

Big tick for the transmission right there. 12 rounds in that test just like a proper boxing match, only 30-35 seconds apiece in reverse, with about 12 seconds of relief on the way down.

I do, however, want to be crystal clear about what this test is, and what it is not. It would be easy to draw the wrong conclusions here.

This is specifically not an accelerated life durability test on this transmission - I cannot tell you how it’ll perform after 100,000kms or 200,000kms. You’d have to perform an a completely different kind of test - a much longer and substantially more complex one - to achieve anything meaningful there.

What this is is a severe-load, high temperature endurance test. Heat kills clutches. And this transmission seems to be very well protected in that respect. You could kill it - I know I could - by simply finding the steepest hill possible and hold it stationary using the throttle. That’ll do it. Just like riding the clutch in a manual. If it’s a hot day with no wind, even easier. You can cook an auto in exactly the same way, it’ll probably just take a little longer.

Of course, the way to protect all clutch-based transmissions is to refrain from slipping the clutch under load. In a dual-clutch, this means refrain from inching forward under load - like uphill.

‘Inching forward’ means driving at any speeds below which the clutch is able to fully engage in first gear. If the clutch is slipping like that, the transmission is potentially in danger.

But obviously it’s impossible to avoid any clutch slipping ever, which is why they (Hyundai-Kia) has built in adequate thermal protection. Pretty much all carmakers do this, expect Ford’s PowerShit, obviously.

On durability, how you drive the car affects the longevity of its components like powertrains and things of that nature. If you go out and do this 12-lap test like I did and you do it every day for the next 10 years or whatever, then your clutch is going to wear out and need replacing sooner than if you’re the dude (or dudette) who doesn’t do this.

This is not the only example. If you do only short trips, your engine is going to wear out earlier, if you never get out on the highway your engine’s gonna wear out earlier, if you drive like a cut snake - you’re gonna wear out your powertrain and brakes earlier than someone much more mechanically sympathetic.

If you’re a tradie who tows a heavy trailer in traffic and puts lots of stuff in the tray all day, every day for the next five years, your powertrain is going to wear out. If you tow a massive caravan around the country for 20,000km straight, your vehicle is gonna cop more abuse than someone who doesn’t. If you heavily modify your vehicle, other bits are gonna wear out sooner.

But I wouldn’t worry about reasonably sloped driveways with this transmissions, as long as you do it normally. It seems quite well designed and you’ve seen the evidence.

In fact, it’s the best dual-clutch transmission I’ve ever driven. It’s the same DCT as in Kia Sorento (as I understand it), and it’s the same one going into the i30 N DCT, after what seems like geologic time.

However, this does not mean this DCT is as refined as a really good, conventional epicyclic automatic - it’s just not. This DCT has some pretty solid logic that drives the decisions it makes out there in the traffic, and it gets wrong-footed a whole lot less than most other DCTs I’ve driven, but frankly, it’s still not perfect.

It’s very good off the mark and at low speeds, and it does a good job when you’re getting away gently in traffic nose-up or nose-down. These are traditional DCT weaknesses, and this transmission has substantially eliminated the freefall sensation which plagued early DCTs - such as when you were reverse parking on a hill.

And before you start with the ‘DCTs are shit’ rhetoric, they’re not.

DCTs are extremely good as sporty driving - they’re great at shifting quickly when they can easily predict the future, and that’s essentially what sporty driving is on an ongoing basis.

SHOULD YOU BUY A DUAL-CLUTCH TRANSMISSION?

Is a DCT right for you? (10,000km test - part 1) >>

Is a DCT right for you? (10,000km test - part 2) >>

This DCT is also brilliant at not running away on you when cruising downhill at a set speed. I tested this in the new North Connex tunnel in Sydney’s armpit recently. It’s a steep downhill entry ramp and the speed limit is 60km/h.

The Santa Fe stayed locked on 60 without running away in the manner of a conventional auto, which is excellent for preserving one’s licence on our over-regulated roads.

DCTs are also very good at saving about 6 per cent compared with a conventional auto and most people never factor this in when criticising the shit out of them. There’s simply a trade-off for these advantages, which is a lack of refinement for mundane driving. Sometimes they get a little wrong-footed, and that rtade-off is very slight in this car.

Most people, probably half, who go out and drive the Santa Fe DCT diesel will never even know that it isn’t a conventional auto. You have to be pretty in-tune with the mechanics and driving process to pick this up.

And the other point to stress here is that you can easily cook a normal epicyclic auto transmission as well, but because of the large circulating volume of oil in there, it’s hard to do that with one slow reverse up a steep driveway or in stop-start traffic.

Cooking a conventional auto is much more likely to occur when towing a caravan at high aerodynamic drag, meaning high speeds (100km/h-plus), on a really hot day for a prolonged period of time, in a vehicle where the manufacturer has cut costs (and cut corners) by failing to put adequate transmission cooling into the design.

Hyundai-Kia has a pretty good track record with DCT durability, frankly. I doubt they’ve gone backwards on this one.

And when you look at Ford and the PowerShit fiasco, the cost of that to them, the class action lawsuits in many countries, and the ongoing reputational damage which flows from this kind of engineering travesty - no carmaker wants to film ‘PowerShit 2.0: Let’s Cook Again’.

Plus, Hyundai does have a 5-year unlimited kilometre warranty and Kia: 7 years, and essentially that means if you drive in a reasonable manner as a reasonable consumer, even with a driveway on the north face of the Eiger, you are essentially covered.

And there’s legislative protection here too, even beyond the warranty, and during - and both these brands are excellent at customer support. They’d like to preserve those reputations.

As I’ve said, I have also had extensive discussions with both Hyundai and Kia about reversing a trailer in similar conditions - which is the subject of my next report.

Just because a ute is cheap, that doesn’t mean it’s worth the money. Is the GWM Cannon more than just a cut-price Ranger wannabe? Can it offer towing, off-roading capability and robust design to compete with the big brand dual-cab utes like Hilux and Triton?