Ultimate Transmission Guide: Manual, Auto, Dual-Clutch and CVT

There are four common transmission types out there, on the road and waiting in the showroom. Without knowing yours, you could easily break something or be abusing it.

CONTENTS:

INTRODUCTION

Despite the showroom floor indicating to you to choose your bipolar transmission - ‘manual’ or ‘automatic’ - there are actually four different kinds of transmissions commonly available today.

It’s important to know what you’ve got, down there, because there are key differences that make them comparatively easy to damage, unwittingly.

If you hand grenade your transmission it could cost you tens of thousands of dollars. So let’s discuss each transmission type and help you understand what yours is and what not to do to avoid having to endure the indignity of picking your bottom jaw up off the service department floor.

.

MANUAL

The humble manual - hardest to use, most difficult to learn, and increasingly rare.

The fundamental flaw: it needs three pedals, and you’ve only got two feet, so that requires cognitive and physical dexterity.

From the top of the automotive heap to the lowest of the low, the manual is an endangered species. Good luck finding a current Ferrari with a clutch pedal.

My top 3 recommended manual new cars

Among cars we mortals can afford, the manual is tolerated as a price leader, but is often unavailable higher up in the model range. Commonly, you just can’t have a manual if you want the leather, the heated seats, the adaptive cruise and the panoramic roof. They just don’t make ‘em like that any more.

The manual is becoming an anachronism - for performance nuts only. And even then, although it’s very satisfying to get it right in a manual, advances in automated transmission technology mean you’ll put in a quicker lap in the auto. You blue-singlet off-roaders take note, also: autos are better at everything now.

BREAKING A MANUAL

The easiest ways to damage your manual transmission unwittingly are to stop at a red light, or in a queue of cars, leave the vehicle in gear, depress the clutch … and hold it there. This really does slash the life of the thrust brace in the clutch - it’s designed to allow you to change gear, not sit there spinning under load for minutes at a time.

Thrust braces are very cheap - just basic axial thrust bearings - but getting to them and replacing them is quite expensive. Also, if you stop like that, with your foot pressed on the clutch, the axial thrust is transferred to the crankshaft, where it goes to work on the crankshaft thrust bearing, shortening its life. The crankshaft thrust bearing is an even cheaper component that is even more expensive to replace.

To avoid this, of course, simply select neutral when you come to a stop, and take your foot off the clutch, unloading the entire mechanism.

Riding the clutch - also a classic mistake made by the mechanically unsympathetic. Friction material in the clutch is not designed to hold the car, while slipping, on a hill. Holding a car on a hill is for brakes. Learn how to do a hill start properly. Riding the clutch is a great way to pump up service department profitability.

And then there’s knob holding. I hate knob holders. The gear knob is not a handrest. That’s what the steering wheel is for. If you rest your hand on the gear knob between changes, it puts load on the selector forks, which shortens their life. Don’t do that.

Put your hand back on the steering wheel, where it belongs, at 9 o’clock. (BTW: If you’re a grown adult still refusing to hold the wheel at 9 and 3, click here >>)

.

AUTOMATIC

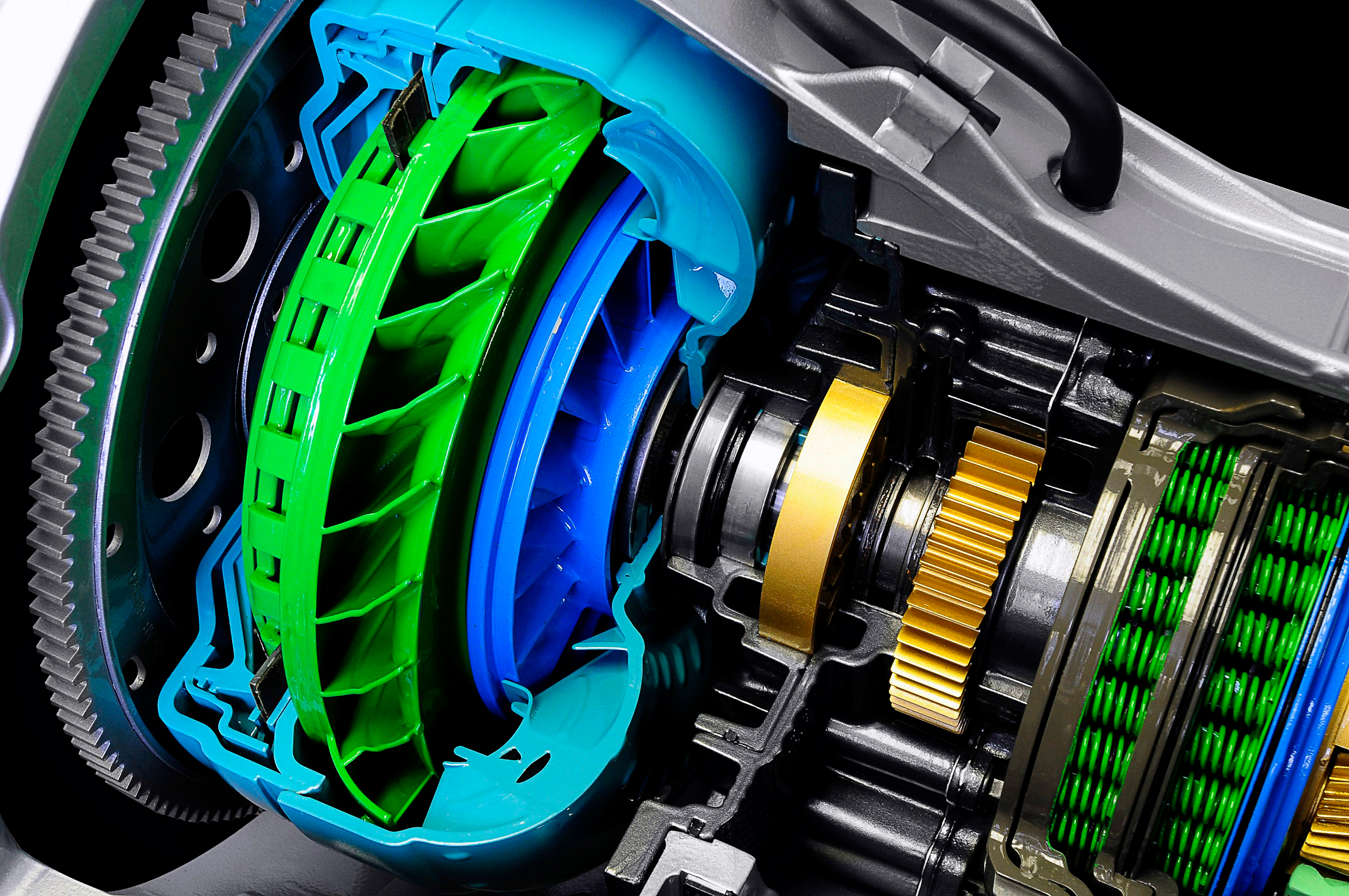

The conventional epicyclic automatic transmission (the infamous ‘slushbox’) remains quite popular - and it does a great job in average cars.

The torque converter - a fluid coupling between the crankshaft and the gearbox input shaft - allows you to come to a complete stop, indefinitely without wearing out or stalling the engine. So that’s nice.

3 new cars with excellent epicyclic automatic transmissions:

Torque converters also allow you to creep forward at a somewhat glacial pace - without consequence. We’re talking inching forwards at the kinds of speeds that would stall a manual in first gear, or require you to abuse the crap out of a clutch.

This is especially useful in SUVs - and especially the ones without low range: you can exploit the ‘slip’ in the converter to go really slow over some rough terrain where the manual would struggle.

The converter also soaks up mechanical shock from changing gear or going from powering to a trailing throttle, and it delivers a nice smooth, refined experience for ordinary driving.

Unfortunately, the torque converter also absorbs quite a bit of energy, and that makes it an imperfect device for fuel efficiency - autos have always been thirstier than manuals, all things considered. And the flipside of that driveline shock-absorbing refinement is: a conventional auto is not the most engaging transmission for performance driving applications.

BREAKING AN AUTO

The easiest way to abuse an auto is to fail to service it. The oil has a fixed life - and it does a big job. Letting it overstay its welcome is a mistake.

Another excellent way to damage an auto is to launch it off the line by selecting neutral, revving its tits off, and then jamming it into ‘D’ for drive. This places incredible stress on the bands in the transmission, which are only designed to go from ‘N’ to ‘D’ when you’re stopped and idling. That little clunk you feel going from N to D? That’s the band engaging.

Bands are quite cheap. They’re just a little bit of metal with some friction material on one side, designed to clamp a spinning drum. But getting to them, and replacing them, is quite expensive. Quite expensive indeed.

If you’re going to launch mum’s Camry - or some other auto - which I advise you never to do - but if you are - the only way to do it is left-foot brake, hard, in ‘D’, load up the throttle and release your left foot. That’s much more mechanically dignified and sympathetic. And a lot cheaper.

.

DUAL CLUTCH

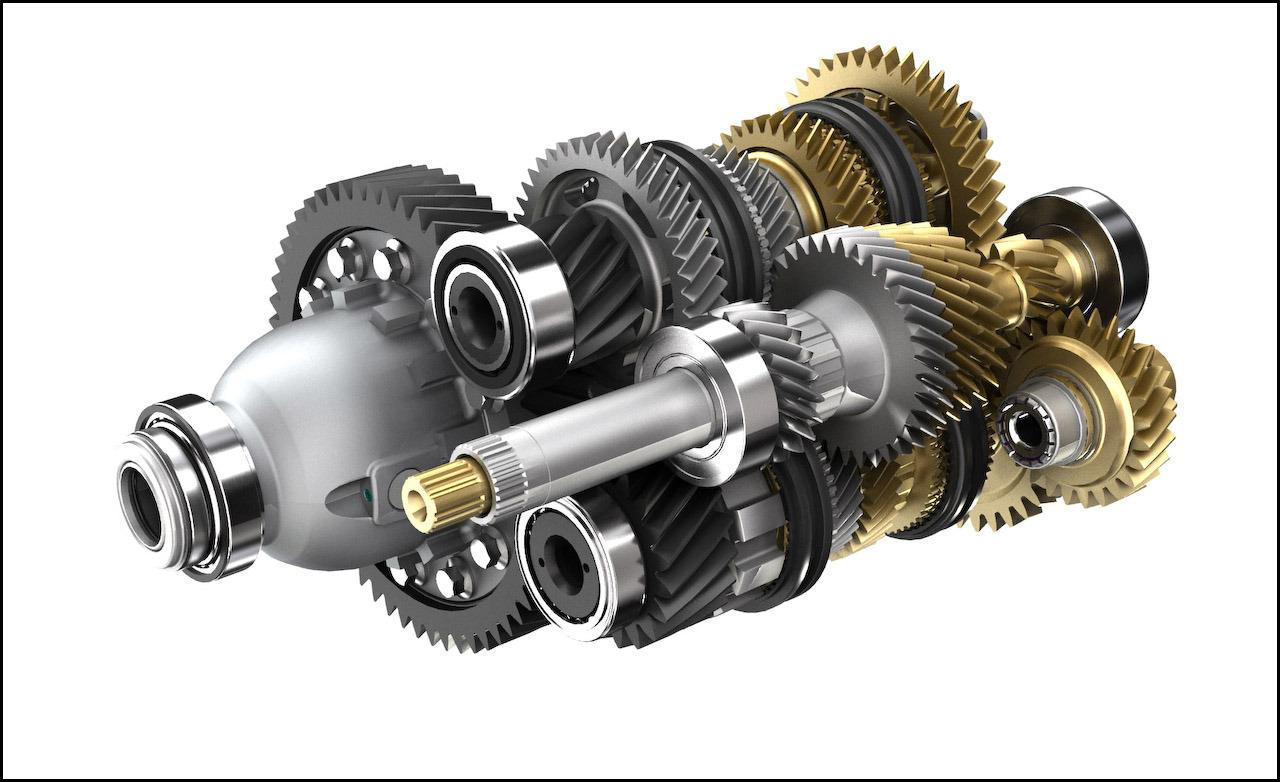

Dual-clutch transmissions seem more complex than a moonshot, and they get so confused - at times - in normal driving. But they are brilliant at performance driving - extremely direct, and fast-shifting.

3 examples of dual-clutch done right:

Hyundai i30 N-Line sedan (Coming soon)

The technical challenge for the software control here is: predicting the future. Deciding what gear comes next: upshift or downshift.

You can expect 6-10 per cent improvement in fuel efficiency compared with a standard auto, and maybe a six per cent improvement in 0-100 kilometres per hour (that’s 0-60 im ‘Murica). And the shifts take place in less than one tenth of a second.

Both Volkswagen and Ford have tried as hard as they could to trash the global reputation of DCTs - Volkswagen with it’s botched DSG recall fiasco, and Ford with its infamous PowerShit, a living nightmare that many a Ford owners experience daily.

But not all DCTs are disasters - the important thing is to know if you are buying one, and drive appropriately. I’ll cover that off in a separate report. They look just like autos from the cockpit - there’s a lever you move from P through R and N on the way to D - and then, the shifts are automated.

How they work

It’s usually easier in performance driving, but it can be difficult in traffic.

See, if you’re up it for the rent, revs skyrocketing, it’s easy to predict the next move will be an upshift.

If you jam on the brakes and the revs start plummeting, next stop: a downshift. In either case, the transmission pre-selects the right next gear automatically. But it’s not always as clear-cut when you’re dithering the speed, brake and throttle in traffic.

The worst thing about the dual-clutch transmission is: Ford and Volkswagen. Between them, these two arsehole automotive giants have done everything possible to torpedo the reputation of the dual clutch transmission.

The Ford ‘Powershift’ transmission, and Volkswagen/Audi/Skoda’s DSG made reliability completely disposable. They just got the design epically wrong - and millions of customers were burned. Ford in particular did a poor job on the design, and iced the cake with a large quantity of ‘don’t give a shit’, which persists to this day. Owners colloquially refer to it as the ‘Powershit’ transmission - not a term of endearment.

The other worst thing about the dual-clutch transmission is - it presents itself to the uninformed driver as if it is just a conventional automatic. The control architecture looks identical in the cabin, and it is an automated gearbox. You could easily own one without knowing, and I have spoken to people in that position.

But it’s a real mistake to drive it like a conventional auto - especially the ‘dry clutch’ kind (like Ford’s Powershit). Let’s get into that now.

BREAKING A DCT

See, in a conventional auto, you can creep along at low speed all day long, with no consequences. But don’t try that in a dual-clutch transmission. Instead of a torque converter, there’s an automated clutch pack that allows driveline disengagement when you stop. So that’s good.

When the light goes green and you’re on the gas, the takeup is relatively smooth. Also good. But if you inch forward, the clutch is forced to slip. And that’s bad. This also occurs in low-speed manoeuvering - uphill reverse parking, things like that. The clutch slips the whole time. Not good.

Extremely not good if you need to reverse a heavy trailer up a steep demanding driveway, to put the boat away every weekend, or something. It’ll feel almost like an automatic - right up to the point where the clutch shits itself prematurely.

Dual clutch transmissions are great for performance cars. Unfortunately, car companies slip them in elsewhere in the lineup, as a matter of convenience, and they provide bugger-all education to owners. I bet at least 50 per cent of the people out there driving dual-clutch transmissions today think they’ve got a conventional automatic.

.

CVT

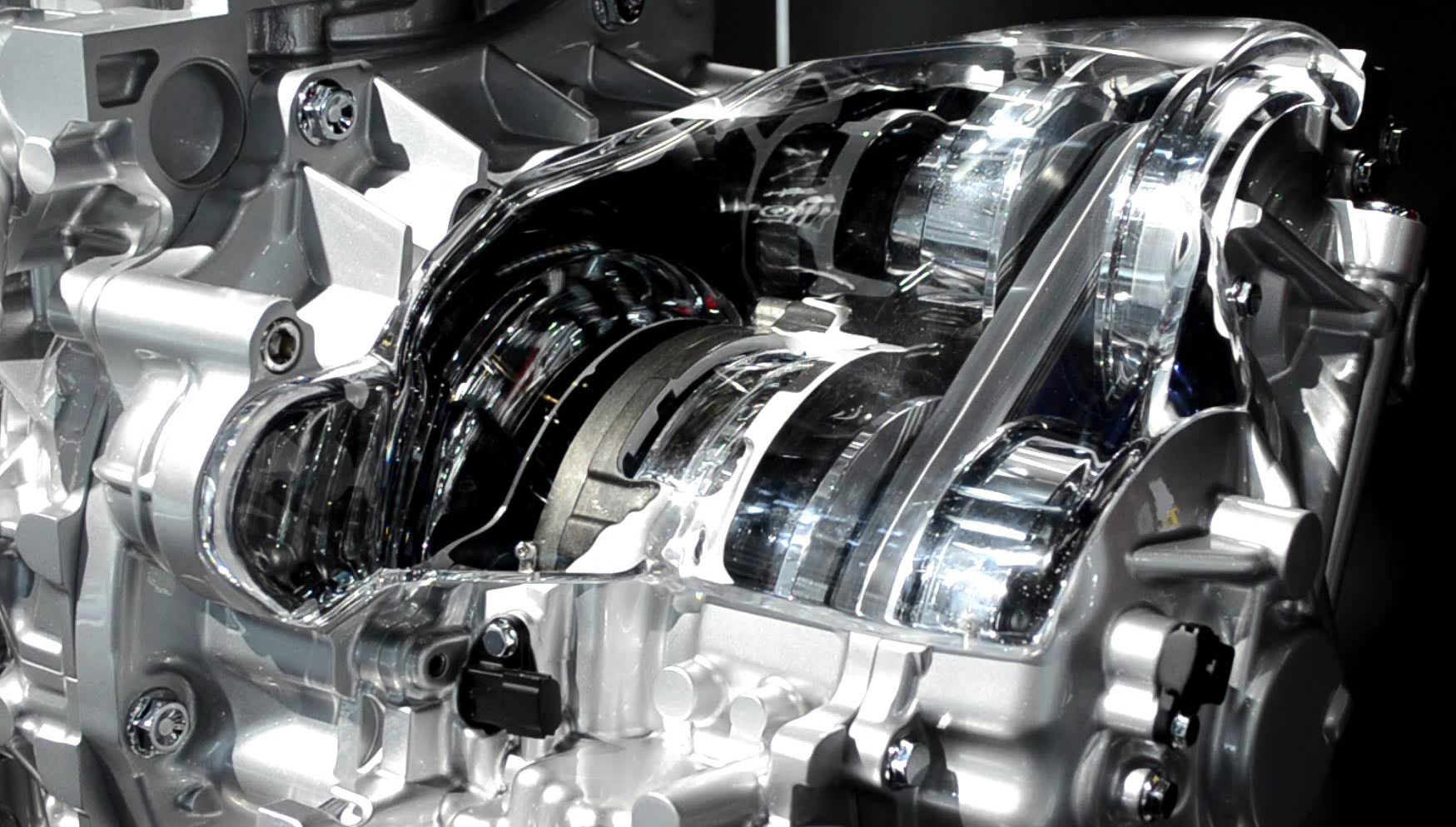

Of all the transmission types, CVT - the continuously variable transmission - gets the worst wrap from reviewers, AKA so-called motoring journalists.

Two points on that:

3 new cars with stand-out CVT transmissions:

First-generation CVTs were pretty awful to drive - and I’m looking at you, first-generation Honda HR-V. At least that vehicle was hateful across the board, and not just in respect of its CVT. Gotta admire consistency.

But, second: car reviewers are as biased as all shit about CVTs, even today. And the most insidious of their biases is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is a scientific trap that works like this: If you think blondes are better in bed, you’re likely to compile a mental list of all the blondes you’ve slept with who were great in the sack, as well disregarding any who were not.

Here’s a quick explanation of how CVTs work >>

You’ll also disregard any brunettes and redheads who were hot, but you’ll tally up those who were not. And this will confirm your flawed fantasy: blonde equals hot; every other hair colour equals not. If you’re a dumb as dogshit car reviewer with no technical training and the consensus view is: CVTs are shit, it’s easy to predict what you are going to write.

You’ll find out some new car has a CVT, and you’ll ignore all the good things about that CVT, and concentrate on the bad. You’ll ignore the fact that CVTs do one thing other transmissions cannot - and it’s kind of important. They can put the engine at exactly the right revs for the power delivery required, and they can keep it there across a wide range of travel speeds.

The easiest example is maximum acceleration. Physics for dummies: Maximum acceleration occurs when the engine is delivering maximum power. That’s a particular point in revs, at wide-open throttle. In every other transmission, you cannot hold the engine at those revs. The fixed transmission ratios mean you climb to that point in revs, you pass it, you upshift, the revs drop and you repeat this process.

You chase, but only very briefly achieve, peak power. Remember when you first discovered pigs have an orgasm that can last 30 minutes? It’s kinda like that. Only… never mind.

Let’s say you want fuel economy, accelerating from 80 to 100 in a particular set of conditions. There’s an ideal engine rpm for that. The CVT will deliver that.

So, in manuals, autos, and dual-clutch transmissions, you cannot hold the engine at the required revs for the job at hand, as your road speed varies. You just cannot do that. In a CVT, you can. This is, perhaps, why CVTs were banned from Formula One motor racing in 1993 - the Williams team had a prototype ready to rip. The powers that be banned it.

The central criticism of CVTs is that they feel different - they hold the revs constant at particular power delivery requirements, as road speed changes. The sensation is the disconnection of increasing revs that conventionally goes with acceleration. The engine just sits there, at the ideal revs, and shit happens. Drive a WRX or Levorg with a CVT and see what I mean. Do it with an open mind.

The problem is: Human nature. Car nuts are inured to the sensation that climbing revs equals ‘shit happening’. CVTs are not like that. They’re better. The very thing uninformed reviewers criticise is the crucial advantage on offer. In many ways, CVT is the ideal transmission.

BREAKING A CVT

Of course, there are technical challenges.

In every other transmission there are physical gears carrying the drive. In a CVT you’ve got a segmented steel belt running on smooth, variable pulleys. And that means the only thing transmitting the drive is shear forces in the lubricating oil.

And that means, you need some pretty special chemistry to make that oil work - we’re talking $200 a litre, and you might need six or seven litres in a transmission, and it might be a good idea to replace it every 50,000 or 60,000 kilometres, maybe stretch it to 100, and I’m not entirely sure many owners are going to be receptive to that.

It’s like, ‘100,000km service: that’ll be a timing belt and new CVT oil. Call it $3 grand’… Durability and service costs are the big criticism, hiding in the wings for CVTs - and very few reviewers mention that.

The other thing about CVTs is - like the conventional auto - they’re almost impossible to abuse, unless you launch them by shifting into ‘D’ from ‘N’ while you’re bounding off the limiter. Just don’t do that.

CONCLUSION

If you’re in the market for a car right now, I hope this helps you crack the kooky code of transmission complexity, and make an informed decision about what’s right for you - and how to prevent it from costing you thousands in unscheduled repairs.

.

WILL TOWING KILL MY DUAL-CLUTCH TRANSMISSION?

If it looks like an automatic, and it smells like an automatic - best not step in it by presuming a dual-clutch transmission is an automatic. And they do present, in the cabin, as automatics - with, for example, the identical control infrastructure. You’ve got a shifter with Park, Reverse, Neutral and Drive, plus two pedals ‘down there’.

IGNORANCE IS NOT BLISS

I’m certain some people buy them presuming they’ve got an automatic - it would be easy enough if you’re not a car nut, not a diligent researcher of such things and - let’s face it - the dealer’s not likely to tell you unless you ask. If they know. They’re there to sell you the car, not educate you, right?

But a dual clutch transmission is not an automatic transmission. And you do need to know. Instead of a torque converter, they have an automated clutch - it can be a wet clutch or a dry clutch - but it’s a clutch, not a fluid coupling. And that means excessive heat from owner abuse - that’s you abusing it - can kill it.

"I am thinking of buying a new Hyundai Kona Highlander 1.6T but I occasionally tow a box trailer to the local tip. Will this affect the DCT in the vehicle as I have seen your video on the different types of transmissions and how to break them?"

- Paul

HOW TO KILL A DCT

Long story short: The most common enquiries I get about dual-clutch transmissions or DCTs - what Volkswagen calls DSGs - are about the Hyundai 1.6 turbo petrol engine in Tucson, Kona and i30 (and also the baby diesel in i30).

Ford and Volkswagen have done a great job between them perpetrating genocide upon the reputation of these transmissions through atrocious design and even worse customer support, but the DCT concept itself is not inherently flawed. It even has significant advantages. Hyundai DCTs seem pretty robust - I don’t get owner complaints about them.

But they can be killed if you presume your DCT is an auto transmission and therefore abuse the clutch. So let’s sort this out.

Kona is rated to tow a maximum of 1300kg (max). A box trailer to the tip will be less than half that (because Kona’s limit for unbraked trailers is 600 kilos), so Paul’s is a very conservative proposed towing assignment. And he’s not going to be doing it that often, most likely - because most people don’t have a trailer-load of used rubber adult products (or whatever) to dump each week.

DON'T 'RIDE' THE CLUTCH

What you need to watch with DCTs is riding the clutch. Obviously the clutch is automated, and the 11th Commandment - the one Moses fumbled and dropped - is ‘thou shalt not inch forward under load’ (meaning: at a speed so low it does not allow the clutch to engage properly in first or reverse).

Because if you commit the venial sin of expecting the clutch to transmit a lot of load before it fully engages, the parts will rub together hard. There’s going to be a lot of heat. And friction-based devices like clutches and brakes all have a limit to the amount of heat they can reject. And when you generate more heat than that, they die.

If you’ve driven a manual you know what I mean. Riding the clutch fills the car with that distinctive ‘barbecued clutch’ smell, at the same time as it fills your monthly budget with a black hole of mechanical accountability.

SPEED MATTERS

Obviously there is a (slow) speed around walking pace below which you need to start to slip the clutch or the engine will start to labour and eventually stall. With the automated clutch in the DCT, at these slow speeds the computer automatically intervenes to keep the engine from stalling by slipping the clutch. This is what you must avoid.

You can feel this easily as you drive on a DCT. It’s patently obvious when the clutch is not yet fully engaged. Especially under load.

The key-word here is 'under load'. Think: trailer-gravity-hill plus ‘slower than walking pace’ equals ‘repair bill you cannot jump over’. I’d suggest the easiest place on earth to destroy the clutch is reversing a loaded trailer (boat, caravan - whatever) up a steep, convoluted driveway.

For the clutch - this is like waking up in hospital and seeing Dr Kevorkian at the bedside. That’s never a good omen.

DESIGN DEFECT?

In my view, this vulnerability to damage is not a design defect any more than riding the clutch in a manual and killing it prematurely is a design defect. So if you kill the clutch this way, it’s not going to be a warranty job.

I do, however, think the car industry really needs to do a better job getting the word out there on this. Saying ‘it’s in the owner’s manual’ is a bit of a cop-out.

HOW ABOUT TRAFFIC?

Remember that this limitation only pertains to inching forward (or in reverse) at a speed so low it does not allow the lowest gear to engage fully. You can drive normally on a DCT all day long with a trailer behind, in stop-start traffic, no problem. Normal takeoffs in traffic - hill starts, etc. - minus the trailer are also no problem. It’s not especially fragile.

I strongly advocate the use of the vehicle's 'auto hold' function to make those hill starts easier. You also need to remember that the transmission - like the rest of the car - is designed in the case of Kona for 1300kg trailer GVMs.

Box trailers without brakes are generally limited to 750kg. In the case of Kona and i30 that unbraked limit is 600kg - and obviously this is a brake-based limitation, not a driveline/DCT durability limit. So Paul’s is a very conservative proposed towing assignment as far as the DCT is concerned.

So unless you live halfway up the Matterhorn and therefore you plan on routinely reversing the trailer up a steep driveway below walking pace, or effectively riding the clutch in traffic, you’ll be fine driving a DCT.

WHEN DCT IS THE WRONG CHOICE

If you do have a steep driveway that is impossible to get up without slipping the clutch (for example) then I think an alternative vehicle with a conventional auto transmission will be more suitable (the 2.0-litre petrol in the Kona, i30 and Tucson has that - as well as plenty of other SUVs I recommend like the Mazda CX-5).

Conventional autos are far more robust in the context of inching forward under load. Because all the transmission fluid in the torque converter has a much greater heat capacity for these low speed, under-load maneuvers.

DCTs: BIG PLUSSES EVERY DAY

And I know I’ve been talking only about the clutch and the DCT as if it’s only a disadvantage here, but overall: au contraire. DCTs have brilliant shift quality for engaged driving - much better than conventional automatics. They make the car perform better and they’re also better on fuel (because they don’t need to power down to shift - this happens in the background on all modern automatics).

Everything in life (or at least in engineering) is a good news / bad news story. Embrace the shift quality, the performance and the increased economy; make sure you don’t abuse the clutch.

It’s really not that hard.