Why the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV is good, but not "ready" for the Outback

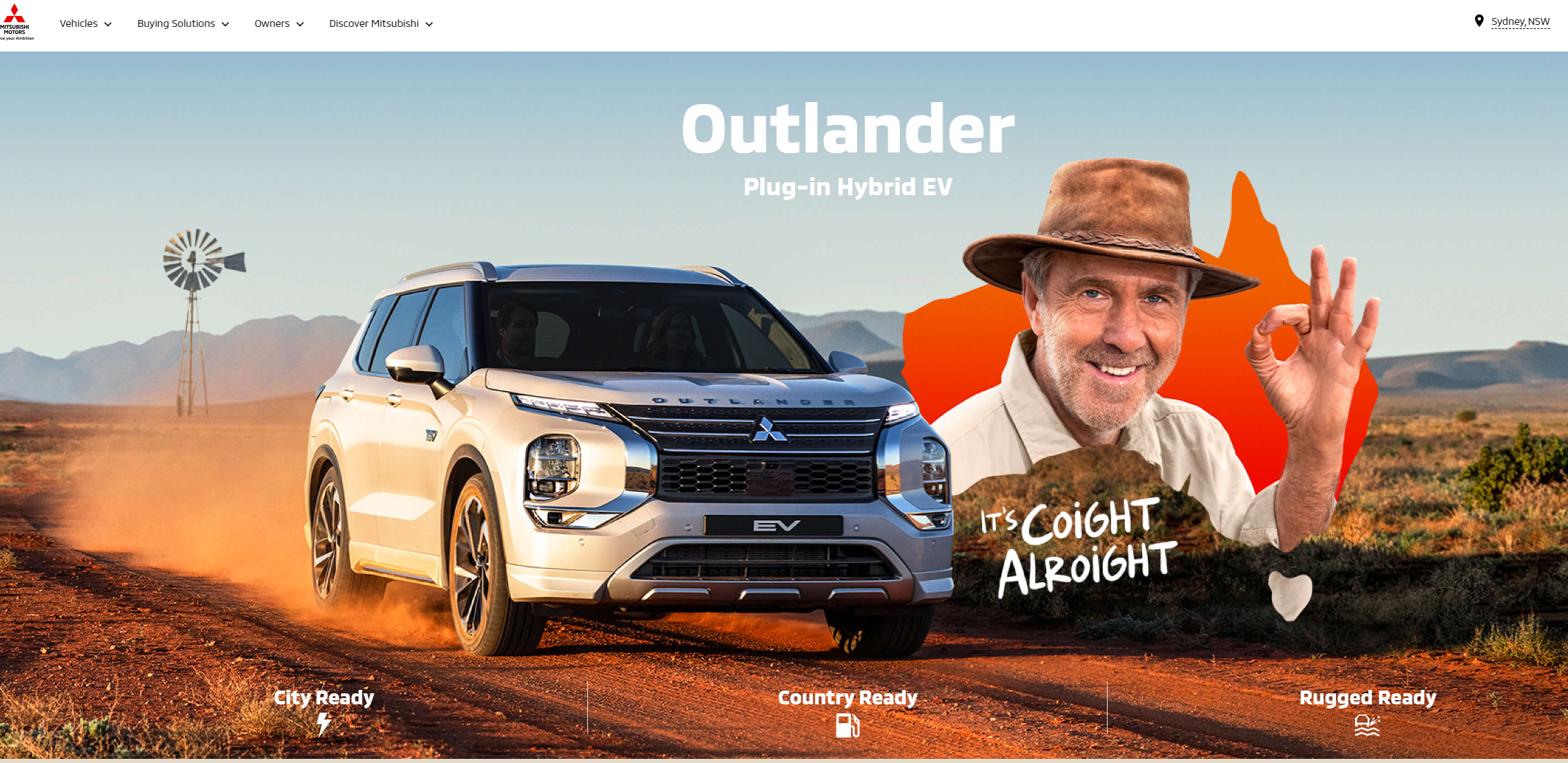

Advertising is supposed to highlight a vehicle’s strengths, but this latest effort from Mitsubishi has taken a wrong turn, seemingly and ended up a long way from home. Here’s why the Outlander plug-in hybrid is not ready for the Australian bush…

It’s easy to think carmaker offices are full of enthusiasts who must all have petrol flowing in their veins in order to work there. You’d have to be a proper revhead to work for a car company, right? Not necessarily.

Counter-intuitively enough, they are often completely divorced from the products which they sell, because more often than not it’s really just an office knee-deep in bean-counters and marketing types that import and sell a bunch of cars here in Australia.

So it's tempting to think that these people are really connected to their car-buying customers, but sometimes they completely miss the point, or lose the plot entirely.

The latest example of this dichotomy is in the new Mitsubishi Outlander Plug-in Hybrid “rugged ready” advertising campaign. See, marketing departments, generally speaking (and not referring to any individuals) wouldn't see any fundamental distinction between something like a car or food, in my view. A product is a product, right?

This leads to some really interesting (mis)communication type phenomena from time to time, one of which is happening right now in the form of highly debatable crackpot claims from Mitsubishi, using the dusted-off slapstick court jester himself, Russell Coight. Remember him?

It's an unlikely ersatz mascot to misrepresent the true strengths of the Outlander PHEV (plug-in hybrid), at least in my estimation.

Mitsubishi has done an absolutely top shelf job photographing/illustrating/photoshopping(?) Outlander PHEV into places in the outback into these properly dodgy, potentially hostile environments where you would absolutely not want to actually take one, especially if you spent your own money on it. I submit into evidence, Exhibit A:

This is the kind of driving the Outlander PHEV is simply not good at, but apparently this is 'quite alright’. Sorry, it’s coight alright:

Have another look at that. You can see the problem here, right? “Rugged Ready”?

City ready? Yeah, absolutely, that’s okay. Country ready? Sure, but just not too far off the beaten track because this is not a Pajero Sport or Triton ute we’re talking about here. It’s a medium SUV for families, with 20-inch wheels, low-profile tyres and no full-size spare wheel in the boot. See for yourself and download the Outlander PHEV specs here >> (Page 24).

In fact, there isn’t even a space saver in the Outlander PHEV - it’s a so-called “tyre repair kit”. The primary issue with these tyre repair kits is they can only be used on a direct puncture through the treadface. And this ‘repair’ is only designed to allow you to limp gingerly to the nearest tyre shop for a full tyre replacement.

If you cop a puncture in the tyre sidewall by hitting some razor sharp outback rock, which is the most common type of tyre puncture in these harsh operating environments, you’re not going to be able to repair that hole.

Is Mitsubishi Australia strenuously suggesting this vehicle is “rugged ready”?

Not only does this marketing effort misrepresent the strengths of this vehicle, but it hangs an entire communications campaign off what this vehicle is just spectacularly not good at doing.

Firstly, it’s ‘Bourke’, located in the north-west of New South Wales, some nine hours from Sydney and very different from Burke who died trying to cross Australia from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria in mid-1861 upon his return.

Next, heading “off the grid” in this manner might suggest you’re out of mobile reception, which is a bad situation if you find yourself with that aforementioned sidewall puncture. You’d best have a sat-phone or E-PERB on you, because it could be two days before you see another human being. Best be carrying water and spare fuel, too.

This notion of “generating its own power during driving” is scientifically illiterate bullshit. Power is energy consumption over time, so the vehicle does not generate its own power; I think they mean ‘energy’. In which case, it does not generate its own magical energy supply, because that is a breach of thermodynamics. What it does is burns fuel in the engine to both turn the wheels, and also directs some of the electricity generated, back into recharging the battery.

However, the problem with thermodynamics is this: we’re all in an energy casino called the universe, everybody must play, and every time you play, the casino wins some. Every time you do a process, like burn fuel, you lose a small bit of energy. Then when you spin an AC electric motor inside an Outlander PHEV, you lose a bit of energy that you started with. And when you spin an alternator to recharge its 20kWh Li-ion battery, you lose a smidge of energy.

So don’t be thinking this is some technological hack that makes Outlander PHEV a self-charging magic machine. It burns fuel to make energy to recharge that battery if you don’t plug it in to recharge from the grid. Next!

To ‘venture up the guts’ in the manner Mitsubishi is suggesting here, is to misrepresent what the Outlander PHEV is actually capable of and designed to do. I don’t think consumers should be venturing, for example, up dry creek beds, like they’ve depicted here:

I don't actually know where the ACCC would draw the line in the sand for misleading and deceptive conduct on this, (we'd probably have to ask Toyota because they seem to be the specialists at this).

However, this next bit seems pretty line-ball, in my view:

With respect to the Outlander PHEV, the beaten track is absolutely where it’s at its best. This is a seven-seat family SUV that is very well equipped, fairly comfortable and drives quite nicely in all suburban environments, while also being able to fun in EV-mode for the daily commute, then drive to Sydney using the existing liquid fuel network. You can even play roadtripping tourist into every quite country town as far as that fuel network and electricity grid will allow.

But suggesting this is some kind of “rally-bred full-time 4WD” is misleading the consumer, in my estimation. They might be able to use one of your seven terrains modes to get out of a sandy carpark at the beach, but outrightly depicting it as suitable for driving through sand dunes (bottom left) is a red flag, in my view.

Then there’s this idea of boiling the electric jug using the 1500-watt outlet in the boot. Now, it is nice to have a vehicle with a couple of power points on board, so credit is due for that, however the total power output capacity of the 240 volt inverter system on this vehicle is not enough for most electric kettles in Australia, which draw 2000 watts. On the balance of probability, the only thing your standard kitchen jug is going to warm up is the inverter, if it doesn’t trip some kind of circuit breaker.

What they should’ve told you is it can charge laptops, phones and camera batteries, maybe some LED outdoor lighting, torch batteries, maybe a camping eski/freezer, the portable speaker for music.

THE REAL SELLING POINT OF OUTLANDER PHEV

Misrepresenting the Outlander Plug-In like this, Russell Coight or not, does not only do potential owners a great disservice but also the vehicle itself.

In my analysis, Outlander PHEV is remarkably technically competent - it's a winner. So instead of dressing its weaknesses up as strengths, fraudulently enough. They could have just concentrated on its actual freaking strengths.

This vehicle is one of the best plug-in hybrids you can own and this is mainly because it has a sufficient battery - it's got big-enough battery capacity to do a lot of running in EV mode, like daily commuting. It's got a 20 kilowatt-hour battery, that's about one third of the battery capacity of a roughly equivalent EV.

It’s a big battery for a PHEV, and packaging that into the vehicle is one of the reasons why there's no spare tyre; it's a compromise the Kia Sorento plug-in hybrid has, with about one third less battery capacity. But Sorento PHEV comes with a full-sized alloy spare wheel and tyre.

But to be fair, I wouldn't be belting it into the outback with either vehicle, but the Sorento just has better remote-area mobility any way you look at it.

Plug-in hybrids aren't designed for that. They're designed for people who live in cities and who do occasional longer-distance regional travel on well-maintained highways. Not “up the guts” of the actual busted-arse outback.

The Outlander plug-in is going to take you 84-ish kilometres, notionally, in EV mode, and then if you decide to drive a properly long way, like several hundred kilometres (Sydney to Canberra, say, or Melbourne to Albury, or even Adelaide to civilization) you can do this without the kind of special ops planning it takes to drive long distances in a full battery EV.

Even when you do that planning, you're going to be anxious the whole time that the one critical charger you need to get home is going to be out of order five minutes before you get there.

Regional commutes are quite okay in a plug-in hybrid. If you kill a tyre, you can just call roadside assistance because generally you're not that far away. You just explain the problem up front, and yeah it's going to be inconvenient, but it's not a disaster. The risk of this happening is less on a decent regional highway anyway, compared with the outback, because the roads are in better condition.

If you want to read a full in-depth technical analysis about the actual strengths of Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, click here >>

I'll help you save thousands on a new Mitsubishi Outlander (incl. PHEV) here

Just fill in this form. No more car dealership rip-offs. Greater transparency. Less stress.

TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES: SPARE WHEELS & TYRES FOR OFF-ROAD ADVENTURE

After reading all this about the Outlander PHEV’s lack of rugged readiness, you might feel inspired to make your soft-roader or your dual-cab 4X4 ute or 4WD wagon even more rugged by fitting your own full-size spare wheel - or two, even. But let’s take a moment to think about exactly what that entails.

Let’s analyse the difficulty involved with attempting to stow a full-size spare wheel in your ordinary passenger vehicle, such as an Outlander, or some other vehicle you perhaps are considering purchasing, perhaps an off-road specific vehicle like a 4X4 ute or wagon.

It might seem like a fairly easy thing to coordinate; calling your local tyre shop and arranging a wheel of X-many inches in diameter, with the correct tyre profile you’ve sourced from the four rubber bands wrapped around the machine-faced alloys in your driveway. You might even just buy a second spare from a wreckers or off a buy/sell site like Facebook Marketplace, eBay or Gumtree. And that’s okay, but there are serious consequences afoot here.

Let’s start with the four-wheel drive off-roading demographic first, because if you’re in this camp, you’re much more likely to attempt this feat of human misadventure.

Okay, so obviously you want at least one spare wheel and tyre if you’re heading off-road, or even just into the regions, perhaps for camping, touring or some nutty driving fun. That’s cool. But how are you going to do this?

A typical 20-inch wheel and tyre weighs at least 25kg - or about the same as an average 10-year-old child. Can you lift a 10-year-old above your head without injury? No? So how do you plan to lift a full-size spare over two metres into the air onto a roof rack, let alone two?

You might therefore consider a rear bar with some kind of tailgate spare wheel holder, or two. Bearing in mind this will add mass to your vehicle’s rear overhang which will make it act as a lever, but secondly, you have to know you can lift those 30kg wheels up high enough to mount onto the carrier’s studs. It’s hard enough getting the studs to line up when you’re changing the wheel down on the ground. But can you do it holding this 30kg mass out in front to line up the holes?

This is an undertaking fraught with potential risk, especially for the typical mid-life beard-stroking 4X4 enthusiast who is somewhat below their peak fitness.

And of course when you’re at speed, that 25kg wheel is also moving that fast, so it carries kinetic energy that gives it momentum in the event it becomes detached from the vehicle. So having a sufficiently restraining system in place on your 4WD is critical. Not only does an errant tyre pose an immediate danger to bystanders and other vehicles, but it has the potential to seriously injure or kill you if you get any of this wrong.

Falling from the roof of your vehicle while attempting to restrain the spare/s is a distinct possibility, and falling two metres or more is enough to leave you paralyzed from neck and spinal injuries, or simply dead from blunt head trauma hitting the vehicle on the way down, a rock when you land, or indeed having that wheel land on you.

You know the film A Million Ways to Die in the West? It’s just like that, only your bogan chariot in place of the horse.

You might feel inclined to fit some kind of cargo barrier to your 4WD wagon or even your family SUV in order to purge yourself of the impracticality problem you face, but this is also rife with a false sense of security.

Fitting a cargo barrier does not necessarily mean that the spare wheel is secure, because cargo barriers are designed to block smaller, lighter items that may become projectiles during a crash event. They are not built to withstand the impact force of a spare wheel, let alone the acceleration loads such a wheel imposes on it during something like a rollover or heavy frontal collision.

Mounting that wheel on the rear tray of your ute is probably the most practical in terms of location, accessibility and ease of operations. But it’s not without risk. The mechanical attachment can be a point of failure, either the device itself, or the canopy arrangement it’s fixed to. There’s also the potential for human error in securing the nuts to the studs, or whatever restraint mechanism is being used, such as straps which can be insufficiently tight enough to hold a 30kg wheel whose mass accelerates with every bump, dip and lateral sway of the body.

Look at how a professional racing team secures two enormous all-terrain tyres to the in-board, low-down position inside the tray of a Ranger Finke Desert truck (above) or the Mitsubishi Ralliart Triton (below). Take note of the thickness of the straps and the robustness of the rachet to physically restraint that mass.

Study the position of this 60+ kilogram mass: Mounted as low as possible, as close to the centreline of the vehicle both laterally and longitudinally. And the slack is tethered neatly into a roll.

While you probably aren’t going to be hammering across the desert in this manner, as a philosophy to follow, this is an excellent example of how you want to be organising some of the heaviest and potentially dangerous items you’re likely to stow in or on your vehicle.

Always try to mount your spares as close to the centre of the vehicle as possible. This keeps the mass-centre as low as possible to maintain dynamic stability, and it reduces the ability for those wheels and tyres to become pendulums, projectiles and potentially fatal in the wrong scenario.

As for adding full-size spare wheels and tyres to vehicles that don’t get them as standard, you’re in a bit of a pinch here. Carmakers don’t like spending money on spare wheels, jacks and wheel braces - the tools are made as cheaply as possible with a absolute bare minimum of life expectancy married into the overall production cost to make the entire vehicle.

So whenever they can offer you a cheap temporary space-saver spare, they will. But that might tempt you to retrofit your own, which can have negative feedback affects. Let’s explore those, like in the case of the Outlander, including both the combustion and PHEV versions.

Firstly, you need to physically inspect the underfloor of the boot compartment (that’s if the spare is mounted there, obviously). Generally speaking, there usually isn’t enough physical space under the floor for a full-size spare wheel. This is common in small-medium hatchbacks and SUVs, and increasingly so in even medium SUVs, particularly those focused at a suburban/metropolitan customer base where tyre repair networks are never far away.

But occasionally there might actually be sufficient space for a full-size spare in a model where, for instance, the base model has a full-size steel wheel (and the higher-spec grades get space-savers), or it could be the reverse in some cases. The temptation might be to simply source a matching full-size wheel and swap it into the compartment under the floor.

What you need to know first however, is whether there is a dedicated restraint mechanism to keep that spare fixed in place - and does it actually fit/reach sufficiently given the additional profile height of the wheel in this compartment. Just because it fits in the hole, doesn’t mean the threaded rod or bolt will reach the captive nut in the bottom of the cavity.

In this same inspection phase you also need to figure out if the boot floor will sit in its original spot as intended. Or is it propped up by the fatter spare wheel? Does the vehicle’s boot floor cover get any kind of additional levels on which you can raise it?

For most utes, large SUVs and 4WD wagons, a full-size spare is generally feasible - but not always. Mazda’s range of large SUVs are burdened with only having space and supply of space-savers, making them fairly impractical for regional touring, even on the beaten track. Be aware of what the spare wheel situation is in your respective vehicle and where it is located.

The spare tyre situation is often overlooked in the car buying undertaking. It’s an out-of-mind-out-of-sight deal for many oblivious consumers who are seduced by the styling and interior, without paying attention to these kinds of details which actually matter in the course of using your vehicle in the big wide world.

Fitting full-size spare wheels to your adventure machine is a potentially hazardous exercise if you don’t carefully research exactly what will work and how you’re going to execute certain plans in the event of a flat. Standing on the top of a tyre, wearing your best safety thongs, in order to get the spare off the roof rack, is such a bad idea. But equally it’s treacherous to be working above the typical height of the average person. Humans can die from even the most mundane falls simply by the most innocuous, yet percussive bump to the head.

There’s a reason UFC athletes lift tractor tyres to work out - and it’s not because they’re something easy or fun to flip. But this is also the reason it’s important that carmakers stop removing spare wheels from new cars >>

Take great care when figuring out how you’re going to extend the mobility potential of your vehicle in remote, rural and outback adventuring, because these are not frivolous accessories you’re tacking onto your mobile home-away-from-home. These are big, cumbersome, heavy but necessary chunks of hardware which have consequential outcomes if fitted poorly.

Think about every possible failure mode for the fitment, carrying, operational logistics and dynamic effects of spare wheel and tyre carrying and installation, and then implement solutions to mitigate those failure modes.

Just because a ute is cheap, that doesn’t mean it’s worth the money. Is the GWM Cannon more than just a cut-price Ranger wannabe? Can it offer towing, off-roading capability and robust design to compete with the big brand dual-cab utes like Hilux and Triton?