Kia Sorento PHEV review and buyer’s guide

If you’re in the market for a new seven-seat SUV, you’ve likely started this process by at least considering some kind of hybrid, EV or similar. So how does Kia’s plug-in hybrid work and should you take a test drive? Here’s everything you need to know…

The plug-in hybrid doesn’t sell in as vast numbers like combustion-only, standard parallel hybrid or even fully-electric vehicles. But that’s doesn’t mean they lack quality or multi-purpose practicality, in fact they often excel at it.

There are many very good reasons a ‘PHEV’ could be the ideal vehicle for you, either as a small step to reduce your fossil fuel consumption, or simply as an internal experiment for your household, or as a legitimately good way to improve air quality.

In this report, we’re going to focus primarily on the PHEV powertrain in relation to the Kia Sorento in particular, and as we go, draw comparisons to its direct rivals like Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV and Mazda’s new CX-60. Then we’ll look at Sorento Hybrid versus Toyota Kluger Hybrid.

Attention:

The entire Kia Sorento model range will be updated in Q4 of 2023, meaning a newer version plug-in hybrid will also be ushered in early 2024. As a result, sales for the current model Sorento (incl. PHEV & hybrid) have been suspended pending the new model’s arrival.

This will not be an entirely all-new vehicle on a wholly new platform, however. So the overall detail and analysis of Sorento PHEV in this report remains valid. This model update will likely be largely cosmetic and what core technical changes are made will be updated upon its arrival in 2024.

Until then, enjoy figuring out if a Sorento PHEV is going to fit the bill for you. If you have any questions, hit the big red buttons and email me for further info.

Download the official Kia Sorento PHEV brochure here >> to check the specs for yourself.

(You might also find of interest my previous review of the Mitsubishi Eclipse Cross PHEV, even though it’s a smaller vehicle and strictly a five-seater.)

There is no question that combustion vehicle sales are not going down anytime soon. Australia bought 546,000 new petrol and diesel vehicles in the first seven months of 2023. In the same period, over 48,000 plain-old parallel or series hybrids were sold in hot competition to 49,000 (almost 50,000 exactly) fully-electric vehicles.

But plug-in hybrids only managed 4366 sales exactly.

Year-to-date sales, July 2023

Currently, PHEV sales make up exactly 0.6 per cent of new car sales thus far in 2023. That’s a terrible statistic for a powertrain that’s supposed to be some kind of bridge between combustion and going fully electric. A best of both worlds that one might think has an intuitive appeal to mainstream car buyers who don’t know they’re quite ready for a battery-powered vehicle but are curious about the next big thing which seems to be going electric.

So what gives? Are PHEVs a poisoned chalice, or are they simply an under-promoted, poorly explained transportation technology? Well, it’s both.

The additional complexity of a plug-in system might come across as an overall drawback to the wider car-buying public. Australians, broadly speaking and my personal opinion, have a somewhat understandable xenophobia toward overly technical things, particularly those we don’t understand. After all, this is the psychological definition of fear - that which we do not understand. It’s why we fear alien invasion, deadly new diseases, and the greater universe - or to some, science in general.

But this fear or undercurrent of cynical malaise for the weird, poorly understood plug-in hybrid is what could be so easily demystified to reveal its great potential to lower both your dependency on fossil fuel, your emissions footprint, and ultimately your fuel bill - while improving the efficiency of your daily life.

But the good news is PHEV sales are on the rise. On a monthly basis, sales improved by 50 per cent comparing July 2023 to July 2022. While Australia bought 5,525 PHEVs in 2022, that number will already have been eclipsed by the end of August if another 800 +/- units sell throughout August; currently 4132 have sold to the end of July, 2023 - a 25 per cent increase over the same period in 2022.

Australian plug-in hybrid EV sales 2020-2023

So let’s unpack exactly why PHEVs work so well, assess and balance out their drawbacks, compare the PHEV to an ordinary hybrid, and see if there are ways in which one of these PHEVs could improve your life, the better for you to make a more informed choice.

Check out my cost breakdown on the Outlander PHEV here: Are PHEVS worth the money: The truth about buying a plug-in >>

PLUG-IN HYBRID: The good

The best aspect of a plug-in hybrid is its multi-role ability to be both a zero-emission suburban runabout to do the shopping, pick up the kids from school, drop into mum’s and commute to work among the stop-start CBD grind.

The three best PHEVs capable of this kind of driving that are actually on-sale and in the market right now are the Mitsubishi Outlander, Kia Sorento and the new Mazda CX-60 discussed in detail here >>

(By the way, notice how the brands who espouse the most green virtue, like Toyota, Nissan, Honda, or which might claim technological clout over the mainstream, like Volkswagen/Audi, Mercedes, Jaguar/Land Rover - none of these brands actually delivery a plug-in hybrid, or at least one that’s within the realm of affordability.)

Without doubt the next biggest benefit of a plug-in hybrid is its ability to perform the aforementioned role of a pseudo all-electric vehicle, while also being a combustion one that, over the Christmas holidays or something, you can drive to Sydney on the normal road network without having to get off the highway and stop for over an hour in some nondescript provincial town you couldn’t give a rat’s arse to see more of.

It can run the kids to school without pumping CO2 and NOx into the open doors of the proceeding kiddy bus, and then be a normal long-distance cruiser.

This aspect of PHEV operation means you don’t have to suffer like owners of battery-only powertrains who get to contend with the crowds queueing up for hours on-end waiting for one of the lowly, poorly maintained public charging stations to become available on a 38-degree day.

Instead of hanging out at the obesity depot known also as McDonald’s and KFC, you can keep driving after a short recharge which should be very quick using a DC fast charger. Alternatively, instead of having to loiter in the rain watching for some enormous EV battery to charge late on a Sunday night trying to get the kids home before starting school on Monday, you can just fill up with petrol and drive onward without having to toil away in the dark.

And when you do eventually have to charge your PHEV battery, you’re only going to be parked for a fraction of the time an empty-battery Tesla, LEAF or BYD is going to be sitting there. You’re up for what we used to call in the fossil fuel heyday as a ‘splash-n-dash’, except for electrons.

Charging at home from 15 per cent to 95 per cent is also going to take a maximum of about 3 hours 25 minutes (so, overnight) if you use the 3.3kW AC charging cable supplied with the vehicle.

This whole arrangement is better than full EVs because charging overnight is convenient, recharging publicly is much quicker and not having to compete with limited array of available charging stations is a better use of your life hours. Plus, it means you don’t get ‘iced’ like Teslas do where some big diesel chariot gets parked in front of your prospective Supercharger with the plug sitting inside the wheelarch.

With your Sorento PHEV, you just keep driving and find somewhere else, because you can just fill up with petrol.

The next bit of good news for the Sorento plug-in is its legitimacy as a proper seven-seater with legroom for actual humans, unlike the strictly kids-only affair in the Outlander PHEV.

The latter has nothing to offer even moderately tall adults, making the additional expense somewhat limited in the age group of kids you can actually get into its row 3. Between leaving booster seats behind at around age 7-8 years old, the point at which a proper lap-sash seatbelt actually sit correctly over their shoulder, and their becoming a long-legged teenager no longer able to physically fit up there, you’re looking at about 3-4 years potentially where row 3 is actually gonna get used. This is okay, but you need to factor in second or third kids and their needs for a capsule; it’s a balancing act, basically, in the Outlander.

But Sorento has much better legroom thanks to an additional 109mm in wheelbase. Now, 10.9 cm doesn’t seem like much when you look at it on a school-issue rule, but it does in terms of how far forward you can slide row 2 in order to better accommodate teenagers in row 3 - especially the ones you didn’t know (until five minutes ago) were coming over after school.

It’s also a massive strategic advantage to have four ISOFix child restraint positions available to you in the Sorento PHEV versus the Outlander or even the Mazda CX-60. So, you’re looking at two booster seats or harnesses in row 3, and two on the outboard seats of row 2, with corresponding top tether anchor points in those same spots, in Sorento.

And of course the CX-60 is completely useless in this regard because it’s a strict five-seater.

Also working in Sorento’s favour here is the better appointed cabin you get compared with the Outlander’s which is noticeably not as premium as the Kia. But you’d expect this somewhat with a $10K higher pricetag.

The Sorento is also a much lighter vehicle overall, at 2091kg in kerb weight (approximating the weight of 47 litres of 91 unleaded). The whole platform drives quite nicely and is well damped over bumps and potholes, where the Outlander is less refined and feels 2 per cent heavier in the corners.

Bad:

There is an intrinsic burden of having to keep your PHEV charged, particularly when you’re in the hustle and bustle of metropolitan and suburban driving. But this isn’t strictly a criticism, it’s just the nature of compromise with plug-ins, as there is with any piece of technology. Or just everything in the universe, for that matter.

Using the battery for your local stop-start trips, the kind that a regular combustion engine hates (ie cold starts), these are perfect for EV-mode in a PHEV - which you cannot do in a plain old hybrid. But if you manage to drain the battery, either by an excess of mileage racked up, or by failing to charge it sufficiently overnight, then it’ll revert back to combustion-only driving, except now it’s running around with a completely depleted battery and AC motor, all baggage that the combustion vehicle has to haul around as a fixed weight penalty.

This costs unnecessarily more fuel than if the battery were charged and contributing to motive power. This is true of all plug-in hybrids. So making sure the battery is charged is a priority, and luckily that’s very easy to do thanks to the 3.3kW AC cable supplied. But you must connect it directly to a powerpoint and should not use an extension lead. Have an external weatherproof wall plug outlet installed by a licensed electrician to make like easier in this regard.

Generally speaking, the lack of a full-size spare wheel and tyre in hybrids, including plug-in hybrids, and fully-electric vehicles, is one major drawback you need to be aware of, depending on your intended use.

Obviously with a PHEV like Outlander or the CX-60 being more compatible with long distance driving compared with a full EV, if you get a flat, getting it fixed out on the road could be somewhat problematic.

Carmakers like Mazda have a lot to answer for when it comes to space-saver spares or deleting spares altogether in favour of ‘repair kits’ like in the $85,000+ CX-60 here.…

If you have an unusual tyre configuration than what the nearest tyre shop has in stock, you could be looking at a hefty tow truck bill. Or if you have a long way to go, you’re going to be stuffed resorting to the so-called ‘tyre repair kit’, which of course, doesn’t work if the puncture is in the tyre sidewall.

Having said this, the Sorento PHEV does actually come with a full-size spare wheel and tyre. This is one of its most redeeming features against the smaller battery capacity and resulting range, compared to the Outlander or the CX-60 - both of which ‘offer’, if that’s the right word, a tyre repair kit.

If you intend to use your PHEV for actual long-distance driving, be it regional, interstate or even just frequent out-of-town stuff where you don’t want to be stuck on the roadside waiting for help, having a full-size spare is going to have you back on the road in a matter of minutes and actually making it to your destination.

There’s also a greater towing capacity with the Outlander over Sorento. Both vehicles have a restricted braked towing capacity compared with their combustion-only counterparts, but Mitsubishi quotes 1600kg (with 160kg of towball download) versus 1350kg on the Kia (and 100kg on the towball). That’s 18 per cent more towing capacity with the Outlander, so you need to ask yourself exactly what work is going to be cut out for this prospective vehicle.

PRICING

Economies of scale dictate that a new product will cost more to make initially, but over time will require fewer input costs as market saturation improves, making it cheaper to manufacture and therefore it can be sold at a more competitive, lower price in order to outsell the competition. This is what you’re seeing with all plug-in hybrids at the moment.

Their low sales volume is due to their higher pricetag. So in order for the price to come down, more units need to be sold to those who can afford it.

The additional expense of a Sorento PHEV outweighs the economical advantage of a more frugal powertrain. We’re talking an extra $12,000 compared with the diesel GT-Line - that’s about 6000 litres of diesel.

POWERTRAIN COMPARISON

Mazda’s 2.5-litre four-cylinder is paired to a 17.8kWh battery which results in 241kW and an official consumption rating of just 2.1L/100km. So how does that compared to other PHEVs in the market?

The CX-60 battery is 12 per cent smaller than the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV’s bigger 20kWh battery pack, so the Mazda offers less EV-mode range, because battery size is proportional to motive power and available distance. Including the 98kW from its 2.4 petrol engine, you’re getting a total 185kW of peak power from the Outlander PHEV, which also has a 56-litre fuel tank that takes 91 RON. The CX-60 takes 58 litres of 95 premium.

So the Mitsubishi offers more range and marginally lower running costs, and it takes about 10 hours to charge from de facto empty (26 per cent state of charge) to full.

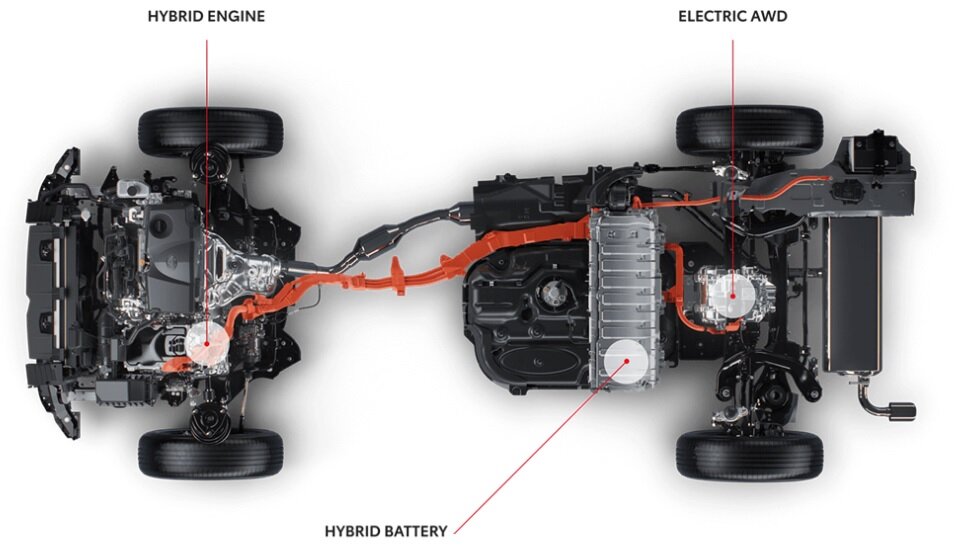

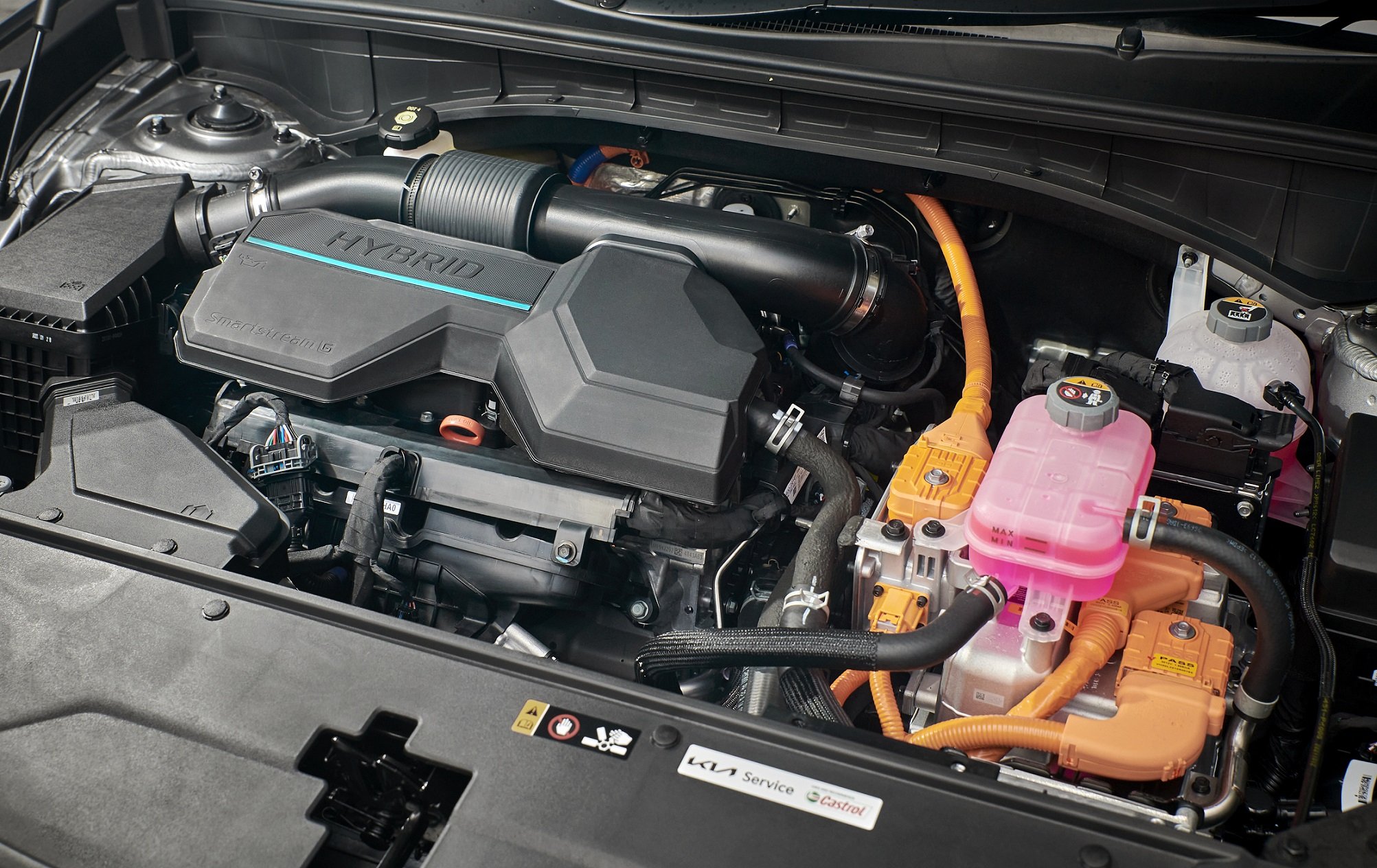

Sorento uses its 1.6L turbo-petrol four-cylinder with a 14kWh battery for a combined 195kW peak power. But it uses multi-point injection on the combustion engine, much like the Outlander, which is why the Kia and Mitsubishi make less power, because they’re tuned for fuel economy whereas the Mazda is tuned for performance using direct injection, despite having a smaller battery.

So to summarise the PHEVs:

Outlander: 2.5L 4-cyl + 20kWh batt. Total 185kW (EV-mode range: 80+km claimed)

Sorento: 1.6L 4-cyl + 14kWh batt. Total 195kW (EV-mode range: 68km claimed)

CX-60: 2.5L 4-cyl + 17kWh batt. Total 241kW (EV-mode range: 76km claimed)

In terms of economy, CX-60 is relying heavily on its combustion engine for its performance edge, and claims 2.5 litres per 100km on the combined fuel test cycle. The Outlander’s bigger battery and multi-point fuel injection gives it a 1.5 litres-per-100km consumption figure, and Sorento claims 1.6 -so effectively the same.

The CX-60 PHEV produces 30 per cent more power than the Outlander, and 23 per cent more than the Sorento.

In the power-to-weight ratios, Outlander PHEV Exceed Tourer has 86 kW/ per tonne, Mazda CX-60 Azami has 120 kW/t, and Sorento has 94.8 kW/t - so right in the middle.

And it’s the same in terms of payload. Outlander: 606kg. CX-60: 544kg Sorento: 588kg. This is after DIY-ing the maths because Kia doesn’t quote kerb weight; so tare of 2056kg + 47 litres of diesel (47 x 0.75 = 35.25kg) = 2091kg kerb wt. approx. GVM - kerb weight = 588). Thanks a lot, Kia.

Having done all this, we’re talking about vehicles that weigh, at their GVM limits, between 2.6 and shy of 2.8 tonnes in the case of the Mitsubishi. Yet all three are using a petrol engine in combination with their batteries, to get these barges going. The problem with this is obvious if you look at any popular dual-cab ute like a Ranger, Triton or Hilux. They’re all diesel. Why?

Diesel fuel contains roughly 30 per cent more energy than the equivalent unit of petrol/gasoline. This is why it’s used to move heavy machinery, it powers trucks, large capacity generators and caravan-hauling, timber toting utes. From an engineering perspective, diesel is the more efficient fuel (and therefore engine) to use when it comes to moving heavy vehicles.

Outlander PHEV does weigh more thanks to its row 3 seating, but only 6kg more.

The misunderstood about PHEVs

Earlier we addressed how the battery and motor become a weight liability if they aren’t charged and working. This is section is about why that happens and how the powertrain actually works in the real world.

Let’s suppose you don’t want to muck around with changing drive modes and you’re quite happy to just slap it into ‘D’ and let the vehicle do its thing. That’s perfectly okay. The powertrain will favour using the battery during high loads, so getting the vehicle moving from a stationary start, for example, from stationary at the lights.

But there’s a dirty big battery, an inverter, an AC electric motor and all kinds of bits ‘n’ bobs which have mass. So if that mass isn’t contributing to driving the vehicle, then two things are going to happen. The weight will be counted as additional load on the combustion engine thereby requiring more fuel to burn to move it.

The combustion engine is going to be directing some of the energy it produces into recharging that 14kWh battery - and in engineering, this is a grossly inefficient way to charge the battery because every time you do a process, you lose available energy, meaning there is an energy tax.

This energy tax is the second law of thermodynamics in play. It means you’re better off just burning only the fuel to move the vehicle than using it to recharge the battery.

Now in the context of driving Melbourne to Sydney, there’s not much you can do in this situation, but at least you can keep the convoy rolling and get to your destination after you run out of battery charge.

SAVING MONEY

Even if you do only ever drive it in EV mode, and that’s kinda difficult, you’re going to struggle just to break even.

Let's say for argument's sake your Sorento is using 12.5 liters per hundred kilometres, out there, in service on urban roads, with you driving. If fuel is $2 a litre, that's $25 for every 100kms, $250 for 1000km worth of money saved if you buy the plug-in and operate it as discussed, only in EV mode. Let’s imagine you’re using ‘free electricity’ from your solar system, too.

Every 4000km is going to be $1000 that you save and you have to save $12,000 grand to break even over a combustion Sorento GT-Line. So you need to drive at least, very best case scenario, 48,000 kms in EV only mode to break even. If you do the average 15,000km of annual driving, you’re looking at 3-4 years before break-even point.

But it’s probably going to be more than that because we haven’t even factored in what you paid for the solar system. And expecting you to only use EV mode is drawing a very long bow.

The good thing in all this is you can pump energy back into the battery using regenerative braking. But be aware that you will never be able to pump in more than you’ve used. It’s more of a consumption delay rather than a strict recharging. You can thank thermodynamics for this.

The important but ultimately misunderstood aspect to buying a plug-in hybrid is that you will be reducing emissions. Not even just CO2, either. Stuff like carcinogens, carbon monoxide, particulates, oxides of nitrogen are all mitigated when you run in EV mode when dropping the kids to school and getting things for dinner.

I'll help you save thousands on a new Kia Sorento PHEV here

Just fill in this form. No more car dealership rip-offs. Greater transparency. Less stress.

PARALLEL HYBRID: What’s good, why they suck and why PHEVs are better

Typical hybrids, like the darlings you see Toyota gushing over, are primarily good for heavy stop-start traffic where acceleration - the most energy intensive part of the drive - is mostly covered by the battery. Usually this is up to about 30-40km/h.

But generally speaking, that’s about as much of the driving as they cover. You cannot put them in EV mode, you cannot recharge them at home or the office, and you don’t get any significant assistance during highway or suburban driving.

Essentially, parallel or series hybrids can only take in one source of fuel, whereas PHEVs can take both petrol and electricity from the grid to then use in a variety of driving situations like overtaking where the combustion engine and battery-motor both contribute motive power.

Hybrids will also prioritise recharging the battery using the combustion engine in addition to capturing kinetic energy otherwise lost via the brakes. PHEVs can do this also, but contribute a great deal more toward actually driving the vehicle. This wider envelope of engagement makes it worth buying a Sorento PHEV for, as an example, over the similarly priced Toyota Kluger.

A Kluger Grande hybrid is just over $80,300 before on-road costs. An additional $1000+/- gets you a PHEV Sorento that you can recharge at home, which you cannot do in the Kluger hybrid. An additional $1000+/- means you can drive in pure EV-mode without emitting a single puff of carbon dioxide, which you cannot do in the Kluger hybrid.

You can read my in-depth breakdown of why a Toyota Kluger hybrid is good and not-so-good, here >>

What does work for the Kluger is its stellar resale value because of the Toyota-factor here in Australia. It’s a worshipped brand and that makes it good at re-sale time because they’re so popular.

Unfortunately, Kluger has only two outboard row 2 ISOFix points for child restraints, although both vehicles get a full-size spare wheel, and the Kluger has row 3 curtain airbags where Sorento does not.

Ultimately however, you are only going to be getting the best use of the Kluger’s tiny 1.8kWh battery in dense city traffic.

The parallel hybrid does offer an advantage in propulsion during the most consumptive step of the combustion engine’s operation: acceleration from standstill. Great amounts of fuel (and therefore emissions) are required to get a 2.1-tonne Kluger from stopped at the lights up to ambient road speed, like 60km/h. But it takes much less energy to go from 60-100km/h because you already have kinetic energy and momentum.

So using a battery and AC motor/s in this 0-40km/h stage is good at reducing emissions, but it only saves a few cents on fuel with every stop-start event. Plus, Kluger hybrids require 95 RON premium fuel, so you’re already paying more for petrol over a 91-happy Sorento PHEV.

This is why a hybrid makes sense in high-density city traffic, where the battery can do as much of the heavy lifting as possible and it gets recharged frequently.

Unfortunately, Toyota uses old nickel-metal hydride batteries which are comparatively heavy compared with lithium-ion. Hence the tiny Kluger battery makes 88kW and doesn’t deliver enough motive power to drive the vehicle on its own. Hence it needs to be topped up all the time.

Also working against the Kluger is its AWD system with a dirty big electric motor at the back. The problem is that motor has mass, but it’s part of an on-demand AWD system that is front-drive biased and only ever goes rear-drive when the computer detects wheelslip or hard acceleration.

So up until that point, or perhaps you put the foot down to overtake something and both motors are working, you’re essentially driving around with a dirty big chunk of extra payload, consuming fuel. This is the same situation as the PHEV with a flat battery adding payload for the combustion engine to move.

Sure, the rear motor can be sent up to 80 per cent of the tractive effort, but until it is being sent anything, it’s a weight penalty until it’s actually doing any work. You can drive using the Kluger hybrid’s battery and motor/s alone, but only in very low demand, gentle cruising situations.

Compare this with the Kia Sorento PHEV which weighs exactly the same as a Kluger Grande, costs roughly the same, but has a big lithium-ion battery capable of 150kWh and can be charged at will by plugging it in at home after delivering about 50km of average commuter driving without ever having to use the combustion engine and emit from the exhaust.

But once you’re on the freeway trying to get up to cruising speed, the Kluger’s battery and AC motors (two at the front, one rear) aren’t doing much work, in fact they’re a liability on the combustion engine unless you tell it to help.

Kluger hybrid isn’t necessarily a bad powertrain design, either. In fact, it’s actually quite good for a number of driving scenarios and it does help reduce emissions in the most energy intensive stop-start driving - and that’s an overall win.

It’s just not quite as broadly capable as the Sorento or Outlander plug-ins, and they do try to make it sound like plugging in is some kind of hassle that Toyota’s magical hybrid system ‘helps’ you avoid, as if consumers are lazy, stupid or both.

We all plug in our phones, out laptops, the kids RC car batteries, we fill up with fuel at the bowser and we can plug in and turn on a lamp without suffering heart failure or rupturing a disc in the lower back.

It’s also worth mentioning the (US-built) Kluger Grande also weighs 100kg more than the hybrid Sorento AWD (built in South Korea).

SORENTO HYBRID

Kia does offer one hell of a powertrain line-up when it comes to Sorento. You can also have a conventional hybrid set-up much like the Kluger, with the choice of front-wheel drive or all-wheel drive.

Download the official Kia Sorento Hybrid brochure here to check the specs for yourself.

Sorento hybrid in either FWD or AWD uses the same 1.6 turbo-petrol four + battery-motor combination, except the battery is smaller, therefore the output is less, and the infrastructure around it is limited - i.e. you can’t plug it in to recharge. The only way to charge the battery is to recover kinetic energy via the brakes or slowing down in general, like the Kluger.

The battery in the hybrid is considerably smaller than in the PHEV, weighing 55kg compared to the 140kg lithium-ion unit in the plug-in. This should tell you it’s a much tinier output as well - just 1 solitary kilowatt-hour compared with 14 in the PHEV. So it’s absolutely only going to be helping you out in the most efficient places possible - those hard starts to get the vehicle going and high-demand applications like overtaking. But don’t be mistaken, it’s primarily going to be the 1.6 turbo doing most of the work.

Driving in normal hybrid mode, like in the PHEV, will see the battery biased toward the immediate acceleration of the vehicle. If you back off the throttle, it’ll usually hang back and still on the battery, but if you pursue the same initial throttle input, or increase it, that will engages the engine to keep it going and/or accelerate at a more aggressive rate.

Fuel economy will be slightly higher on the AWD system than the front-wheel drive, and you’ll also have uneven tyre wear rates choosing the front-driver over the AWD, so rotating tyres will need to be done at the necessary times.

As for driving these two, it’s not unfair to suggest test driving the Kluger first because once you get into the Sorento you will immediately know which is the more premium vehicle. Kluger is fundamentally an American vehicle so it rides very softly, and uses a lot of real estate. The Sorento is a much smarter packaging effort, but at least they both get full-size alloy spare wheels, which is a bit unlike Toyota to be so generous.

The Sorento is a much more taught drive thanks to locally tuned suspension on the platform, making it much less floaty in corners and it doesn’t feel as heavy as the Kluger.

Ultimately, the Sorento is backed by one of the best brands for aftersales customer service in Australia - up there with Hyundai and Subaru. Kia, generally speaking, makes a clear effort to do the right thing by the consumer when a legitimate problem arises and the conditions are met to turn their frown upside-down.

This current generation of Sorento offers a wide range of powertrains and while the hybrid is a bit lacklustre in the performance stakes, that’s missing the point of such a vehicle and the kind of consumer it’s designed for. Using multi-point injection is not designed for performance, so don’t expect this big seven-seater (or its rivals) to drive in a sporty manner. That’s a different usage case.

Sorento PHEV and hybrid do a pretty good job at mitigating combustion from the acceleration sequence of mundane daily family driving, and that’s exactly what this vehicle genre is designed for. It’s an excellent bridge between the full-blown big-battery EV you might not quite be ready to stump-up for, and the combustion past you’d like to move on from.

And if you drive like a normal person in traffic doing the ordinary things any seven-seater is designed for, you’ll contribute fewer emissions to the air we breathe, and that’s a win for not just you, but everyone else.

Just keep that plug-in battery charged.

The Santa Fe offers a hybrid powertrain in one of Australia’s best-selling seven-seat SUVs, you get premium European-style refinement and the equipment you’d expect from prestige brands, keeping its value proposition and family appeal.