How to prevent a towing sway disaster

In the video below, the driver towing a boat loses control and smashes into the guardrail. Here’s how to prevent that.

Basic towing principles

Heavy trailers - pig trailers, with centralised axle groups - like caravans, boats, horse floats, etc., are essentially unstable in yaw and pitch. This is not a problem on light trailers, but it certainly can be on the heavy ones.

As shown in the video above, it doesn’t take long for trailer sway to take control of directional stability. Dashcam footage, in this case, provides a great learning tool. Basically, it goes like this; dude towing a decent-size boat overtakes two cars, boat gets caught up in turbulence, horizontal movement follows, dude ends up on his side with the boat in front of him.

‘Pig trailer’ design relies on the underlying stability of the towing vehicle towing it to keep things under control in those rotational planes. So, the bigger the trailer, relative to the vehicle, the easier it is to lose control, which is why I think towing 3.5 tonnes with a ute is so insane - despite the manufacturers saying it’s OK, and the regulators allowing it.

And, towing a big, heavy thing like that, at 100km/h is also insane. Even with a Landcruiser or a Patrol. Insane.

It’s rare to catch this kind of event on video - so, rather than have a laugh, I really see this as an opportunity to stop this kind of thing happening to you, or around you, as you drive down the highway.

What causes trailer instability?

This crash actually starts when the boat draws up alongside the two vehicles as it overtakes, at about 100 kays an hour. This is a classic venturi. Kinda like in a carburettor, only horizontal. You’ve got high-speed relative airflow between the vehicles on the left and the ute and the boat on the right.

That sets up a negative pressure well between the vehicles on the left and the boat and the trailer on the right - as evidenced by the boat clearly being sucked left, towards the vehicles, as it passes them. It lurches this way twice - clear as day - each time it passes one of those two cars. And that’s all it takes for disaster to ride on in.

The low pressure is doing the sucking, and the fact that the trailer is unstable in yaw allows it to rotate horizontally in this way. Instant pendulum. There’s really nothing the driver can do about this - except of course know this danger exists up front, and refrain from doing the overtaking move. Clearly, ignorance is not bliss.

Boats are heavy at the back, too, so the boat becomes a heavy compound pendulum hanging off the ute. I don’t even know if the driver had time to get terrified.

It’s 11 seconds from that first lurch to the point where the ute rolls over. I suppose it seemed longer than that, to the occupants. But it’s only six seconds until the first impact. It’s hardly a lot of time for emotional engagement. I suspect the driver was just reactive during the process, but quite shaken afterwards.

I imagine him fighting each lurch to the side with a counter-steering move - like, a bit of opposite lock - which, unfortunately, in this case, just feeds back into the system and makes each subsequent lurch of the pendulum even bigger.

Four-and-a-half swings into it, after the very first left lurch, the right edge of the trailer hits the guard rail. But crashing was a done deal six seconds before, in terms of the process.

The amplitude of the pivots is still increasing after that first impact, and the guard rails just do a superb job. They prevent any impact with trees, and the combination doesn’t slip down into the gully. So, well done there, civil engineering.

There are actually four separate guard rail impacts, and there’s a lot of sliding sideways towards the end - both of which extend the time duration of the collision and reduce the loads on the participants. In other words, that part of the system functioned exactly as it should have. I’m talking about the road infrastructure.

And, fortuitously, nobody was coming the other way at the time, and it appears nobody was hurt. Pretty terrifying experience for the dudes who were overtaken, too, I imagine.

How to prevent this happening to you

So, what can we learn from this? Here’s six preventative towing tips.

Number One: Minimise the mass of the trailer relative to the vehicle towing it. I know size matters, but when it comes to trailers and safety, smaller is definitely better, and it terrifies me the people who e-mail me direct and say, basically, that they want to tow three tonnes with the smallest vehicle possible, because it’s also their daily driver.

That’s nuts. If you want to tow a heavy trailer, get a heavy vehicle. This is the fundamental stability solution. Personally I think it’s fairly insane to tow a trailer heavier than the kerb mass of the vehicle towing it. I bought a trailer recently with a two-tonne ATM for the Triton GSR, for exactly this reason. It’s the heaviest trailer I’m prepared to tow with that vehicle, despite its 3.1-tonne tow capacity.

I’m conservative like that - mainly because I don’t want to wake up, parked on the side, in the middle of the road, with the trailer in front of me. Call me old fashioned.

Number Two: Get the trailer and the vehicle set up right, with five to 10 per cent of the loaded mass of the trailer as the static towball download. That’s ideal for stability. And boats are so difficult here, because the heavy components hang off the rear. Measure the weights - do not guess, or read them off a spec sheet. Visit a weighbridge and do this right.

Number Three: Drive conservatively. That means, knock 10 or 15 kays off how you’d normally drive (conservatively). It can feel quite OK towing heavy at 100 - but it can also come unglued very rapidly, as you’ve seen. Just change your mindset here, and for Christ’s sake, let faster vehicles past at every opportunity. There’s no need to ramp up the tension on an already struggling road system.

Number Four: Leave some ‘acceleration juice’ in the tank. Meaning: one of the reasons the driver of this ill-fated towing assignment crashed out is that if you drive a trailer and it starts to get the death wobbles, the best move is: accelerate gently and don’t try counter-steering. (Because acceleration reduces amplitude, and counter-steering often causes the amplitude of the subsequent swing to increase - and you only get about four swings until it’s all over, at speed, right?)

Our ‘hero’ here was accelerating at the maximum potential of the vehicle for the overtake. And, with no more acceleration juice in the tank, he was unable to gently tug the pendulum forwards, to reduce the amplitude of the next swings.

Number Five: Get some driver training. This trains you to look as far down the road as possible, which is generally where you want the vehicle and the trailer to go, in that order. Under pressure, you generally steer where you’re looking and it’s less likely you’ll over-compensate with the steering.

It goes without saying you need to have both hands on the wheel at nine and three, not be half asleep, have the seat properly adjusted, and the mirrors, be situationally aware, and check your tyre pressures. That’s the price of admission. I should not have to say this. And yet, here we are.

Finally - Number Six: If you’re upgrading the vehicle, get one with a ‘trailer anti-sway’ algorithm built into the electronic stability control system. Computers are generally better at this than most/all drivers. Not only do they detect the problem and intervene sooner, but they also intervene better, by cutting power when it’s needed and applying the brakes to individual wheels to generate the yaw response needed to cure the problem.

Note that I did not just say: ‘Get trailer sway control and then it’s OK to go back to driving like a dick.’ The safest systems are the ones with the best systematic safeguards available, and the highest level of operator vigilance as well.

Reacting to your trailer crash feedback and commentary

Responding to your representative feedback on trailer sway and general heavy hauling highway mayhem.

I got a heap of interesting comments from you (collectively) on that dude who threw his boat into the weeds.

These comments orbit around the report above on this disaster and how to prevent it, which (if you’ve not seen it) you can detain yourself by viewing now … I will of course wait, with infinite patience.

The most interesting comment that came across my inbox was from Douglas Miller:

Thank you very much, Douglas Miller. Audiences are a fantastic brains trust. Just awesome. See, that’s a really interesting piece of previously unknown information. Boat moves back. Trailer gets less and less stable in yaw. Makes complete sense. Driver even notices this increased propensity to sway, and yet (and this really does my head in):

There’s no evidence that he stopped and investigated the problem. Maybe he did, and he found nothing. But (I’m really trying to be charitable here) if he noticed sway starting at 100, why not just remain below 100? You know, get back home safely and take steps to get a mechanic or a trailer joint to sort this out.

Noticing sway - which is rock-solid evidence of instability - and then driving like that is … words fail me. It’s not logical. It’s certainly not responsible behaviour.

If the trailer’s not properly load balanced, any external influence, like the Bernoulli/venturi effect on overtaking, the transverse crown - whatever - well, you’ve seen the result.

Pressing on, in the face of this evidence of a major problem, if what Mr Miller says is correct, is incomprehensible to me.

The Nutcracker

Paul Cromwell now:

Paul, Paul, Paul ... I think you mean ‘case in point’. Measure twice, and cut once, dude. He’s not done yet:

I said ‘accelerate gently’, ‘gently’ - and keep the wheels pointed ahead. Don’t counter-steer, because it will feed back and increase amplitude.

If you keep the coupling under tension, by accelerating gently (keyword: ‘gently’) you reduce amplitude. If the coupling goes into compression, you will increase amplitude. #physics. Don’t accelerate aggressively.

Paul goes on:

Easy on the exclamation points, dude. That’s a lot of shouting.

Firstly, I don’t think there’s been all that much law reform in the laws of Newtonian physics, between many moons ago and now. But just so you don’t think this is a matter of opinion, this is the official advice from the NSW road regulation mob: rms.gov.au link >>

So, I’d just like to make an important point on this. It’s applicable to all loss of control and skidding, sliding events - not just towing tank-slappers.

There’s a phase of these incidents where the event is potentially recoverable, and disaster may be averted if you get this right. So, in this phase, accelerate gently, to keep the coupling in tension, keep your vision up and oriented where you want to go, both hands on the wheel. Hope for the best.

But if you transition to phase two, and you’re crashing, or inevitably about to crash, brake, and brake heavily. Like, attempt to snap the brake pedal off and push it through the floor. If you are going to crash, the best possible outcome generally happens at the lowest possible speed. (Balance of probability.)

Some criticism of the venturi effect that led to this crash, now, from Nooch 86:

So, Nooch, this is perhaps not a fair fight, because I am a kind of scientist, inasmuch as engineering is exclusively an applied science, but I’d suggest that the relative speed between the boat and the cars is insignificant to Bernoulli.

What sets up the venturi is the speed difference between the vehicles on either side, both doing about 100km/h, and the air between those vehicles, which is roughly static. So there's that...

That’s a venturi - the Bernoulli effect - and the hull of the boat is incidentally, a perfect-ish shape for this. So there’s that.

Here’s Nooch again:

You cannot see the tow vehicle doing anything at that time. It is obscured by the boat. What you have there, dude, is - at best - an interesting hypothesis. He did run a bit wide to the right initially, probably a lurch as a result of crossing the transverse crown in the road, and this may well have been an additional contributor to the crash.

Then the venturi kicked in, twice, and crashing was basically inevitable.

KOITO ROB chimed in:

The wheels don’t go off the tarmac. They go beyond the white line demarking the edge of the lane, but they stay on the bitumen. So there’s that.

Am I sure? In the domain of science, there are observations you can make from the video, and hypotheses you can advance, which are consistent with physics. There’s no single cause here - unless you want to say ‘he overtook too fast, in the wrong spot’. That’s absolutely true.

But what we’re looking at here is a confluence of contributing factors. Douglas Miller’s point about the load shifting rearwards is tremendously significant, predisposing the trailer to excessive sway.

He ran a little bit wide crossing the transverse crown. Then he ran into the Bernoulli Effect (the venturi thing) - he was going too fast to recover - and crashing was a done deal.

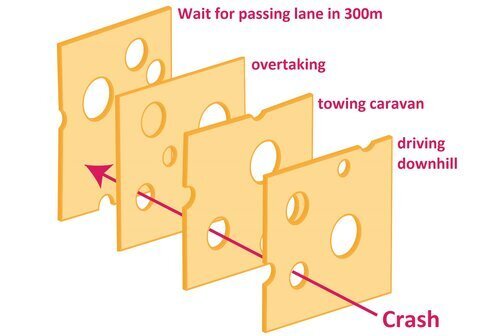

There’s a dude named Professor James Reason - you can look him up; he’s the father of disaster analysis - he coined the infamous Swiss Cheese theory, which says risk factors are like slices of Swiss cheese. You throw them up in the air, and if the holes line up, a disaster steams on through. But if you move one or more one of the slices, by mitigating risk, there’s no pathway for the disaster to occur.

So if he’d stopped and checked the trailer and discovered the boat had slipped back, and fixed it - no disaster. If he noticed the added sway and kept the speed down, refrained from overtaking like that - no disaster.

I’m pretty sure my hypothesis is on the money - or close - but learning, via the comments that the winch was loose and the load had shifted - also hugely significant.

So I urge you, in considering these kinds of issues, and safety on the road generally, to think in terms of risk factors and not causality. The thing to do is mitigate as many risk factors as possible. Don’t give your potential disaster viable a pathway through all that cheese.

David Hughes now:

Dude, In other news: the sky was blue and the trees were green. When you are on the highway, heading towards a bridge over a gully, you are going downhill, because … topography. There’s no bridges over gullies on the tops of hills. Generally. Not in that kind of terrain.

The main reason why these crashes happen downhill is that, in many vehicles, the powertrain limits uphill performance when you tow. Because you’re battling gravity. This is quite frustrating for many drivers, so when they get to a downhill section, thanks to the hi-tech miracle of gravity assistance, they enjoy the liberation of being able to power back up and accelerate to 100 or beyond…

This feels great, but it opens the door to dynamic instability, and it also pisses off the world and his brother, who have been held up behind you on every uphill section and now, they can’t overtake downhill without speeding and risking a fine. Because you’re driving like a big bag of dicks.

If you’re towing something heavy, drive at 85 or 90, maximum. Don’t speed up downhill just because you can. It opens the door to events like the one you’ve seen here, which you really don’t want to have a starring role in.

Here’s an interesting take from a dude (presumably), named Dunk:

I agree with all that - hypothetically. But only hypothetically. See, there’s a huge practical problem with applying the trailer brakes. It sounds so simple, if you’re an armchair expert, and it will work. But…

Imagine yourself as the pilot of a large jet with hundreds of people onboard. All those lives in your hands. You’re cleared for takeoff, on the ground roll. Full throttle. You get to V1. You rotate. You’re watching the ASI, looking for V2 and positive rate of climb. Then you’re gunna put the gear away and look for three green lights. ‘Cuz that’s how this works.

You just hit V2. Without warning, engine two fails catastrophically. Maybe it’s on fire. You don’t know that yet. You have to do exactly the right things, immediately, or everyone dies. Below V1, you land. Above V2, you must fly out of the airfield. They’re completely different processes, requiring completely different actions from you. Over to you. Your response to this threat has to be immediate and instinctive, and correct.

The reason everyone doesn’t die when this happens is: you’ve done this many times in a simulator. Maybe hundreds. Doesn’t even raise a sweat. You just do it.

So, go back to towing the boat. You’re in the middle of this ‘sway from hell’ event, which you were not expecting. To activate the trailer brakes, which sounds so friggin’ easy, you either have to know, by virtue of rock-solid muscle memory developed by endless practise, exactly where the switch, lever or dial is, without looking at it, you have to know which way it moves, and you have to do it. Without hesitation.

If you’ve practised this a few hundred times, no problem. It’s like slipping a punch in the boxing ring - it just happens. You don’t think about it consciously. It’s a ‘flow state’ response.

But, if you haven’t practised, you’re in an OODA loop: Observe, Orient, Decide and Act. You might not get to ‘Act’ - because your IQ is in freefall. (We’ll get to that.) If you do, you need to take your eyes off the road and orient yourself to the switch, and figure its operation out. Good luck with that…

Especially since your own biology is betraying you. In this situation, evolution is flooding your body with stress hormones. Your peripheral vision is shutting down. There’s a massive vasoconstriction response. You lose the circulation in your extremities. Your arms go like lead. You lose fine motor control in your fingers. And you lose about 60 IQ points. You are not going to be able to figure this out in the moment without considerable, repetitive preparation/training.

It’s just like being attacked. You do not rise to these occasions. You fall back on any training you’ve done. Or you die. There’s a cheery thought.

This is why I do not recommend applying the trailer brakes as a solution. It’s very effective, but unfortunately, most drivers are not smart enough, not disciplined enough and not diligent enough to train themselves to respond to this threat in this way, automatically. Trailer brakes: Great idea. Hypothetically. In reality, for most drivers, it’s a fantasy.

Gerard Opperwal now:

I don’t think you should accelerate aggressively, but you should keep that coupling under tension. I think we’re in furious agreement that you should maintain a conservatively low, safe speed, even if you are getting an egg-on from gravity, going downhill.

To be perfectly clear, the crash we’re discussing is a done deal the moment Bernoulli dropped by. There is no getting out of it. But if you are driving conservatively and sway kicks in, keep some gentle accelerative tension on the coupling, and hold the wheel straight. If you can instinctively apply the trailer brakes, because you’ve practised it with OCD, do that.

Then pull over safely and check the trailer for obvious defects like low tyre pressure or the boat shifting back.

Bob_778 now:

Okay, so, I’m going to assume that last crack was a joke - because you simply do not enjoy a moral imprimatur to drive like a card-carrying cock, in any situation. You just don’t. If someone’s moving slower than you on the highway - wait (wait endlessly, if necessary) for a safe overtaking opportunity.

Patience is a virtue, dude, and no more so than on the highway during holidays. Some guy in front of you towing a caravan at 85 in a 100 zone? He’s keeping himself and everyone around him safe. So, don’t be an arsehole.

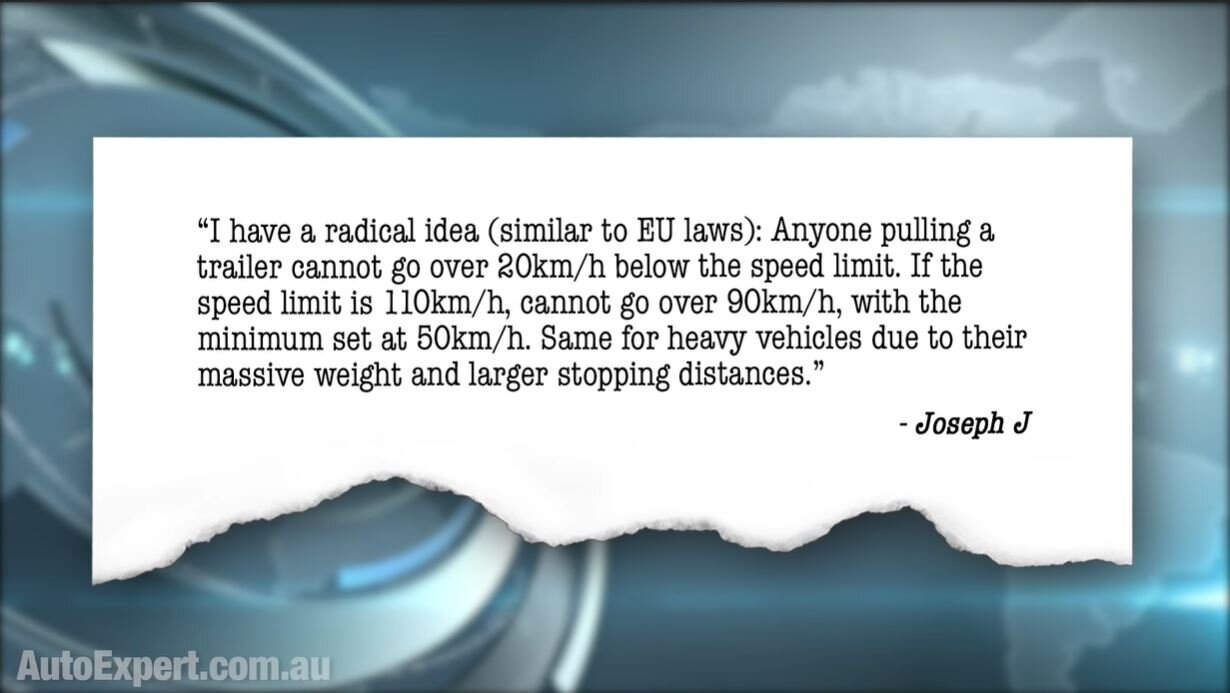

Now a suggestion from Joseph J:

Yeah - good idea. The reality is: Mandated lower speeds for towing are not generally a legislative thing for Austalia. Nor is there a requirement for additional training.

In WA, the absolute limit for towing is 100 - even if the posted limit is 110. In NSW if the GCM is more than 4.5 tonnes, your limit is 100 - even in 110 zones. So that’s, like, a ute with a 2.5-tonne trailer. Kinda thing.

Posted limit applies in Tasmania (up to 12 tonnes) and it’s posted limit in Victoria, the ACT, Queensland, NT and SA as well. So - no special speed provisions there, at least, not that I could find.

Some manufacturers have maximum speeds for towing - Subaru did and maybe does still (I haven’t looked recently). It used to be 80km/h for Subaru. Ford did that kind of thing on the Territory as well. For 2700kg+ it was 80km/h. At 2300 it was 85. For 1600 kilos it was 95. So, read the owner’s manual.

But more than that - just drive conservatively. Towing a big, heavy thing is not a trivial pursuit. If you’d normally drive conservatively at 100 in some particular conditions, unfettered by the trailer, knock it back to 80 or 85 in the same conditions with the trailer, no matter how rock-solid it seems.

Because as you’ve just seen - you’re close to the edge. You can transition from in control to out of control very rapidly when you tow something heavy. And it feels great … until it doesn’t. In between those two states, the opportunities for recovery of control are limited, at best.

Kia Sportage is a strong-value medium SUV that can handle both family duties in the suburbs and regional holiday travel. This affordable, reliable and well-equipped five-seater also offers two excellent hybrid or diesel powertrains.